|

www.johngill.net

|

Page 1

|

www.johngill.net

|

General History - A Very

Brief Overview

Where and

when did documented

bouldering start? Some

think it began with Chris Sharma in the early 1990s. Others believe it

started with me in the 1950s. Still others think that Pierre Allain and

his 'Bleausards initiated the sport in the 1930s. In

fact, climbers were scrambling about on boulders in Fontainebleau as

early

as 1874. Does scrambling and easy climbing on boulders constitute bouldering?

If so, then the 'Bleau climbers may have been the first to document an

appreciation

of the sport.. . . Traditional Bouldering Undocumented

boulder climbing or bouldering - depending upon your definition - may

have been practiced as early as the mid 19th century when alpinism

began to flourish. Swiss guides and clients

likely spent many a rainy day on the boulders rather than venturing

forth onto the

high peaks. Both guides and amateurs probably exercised on small local

rocks and outcrops even in fair weather.

Not only did the early 'Bleausards record their activities, but these activities - whether with top ropes or not, as generation after generation of Parisian climbers made the short journey to Fontainebleau to practice for the Alps - continued in a more or less uninterrupted fashion until present times. This temporal continuity appears to be unmatched anywhere else, although the most important advances in difficulty at Fontainebleau occurred after 1970. A more serious version of early bouldering - and one not restricted to a particular area, such as Fontainebleau - appears to have started in Great Britain in the 1880s, championed by Oscar Eckenstein - a short but sturdily built gymnastic climber capable of one-arm pull-ups. Aleister Crowley speaks of Eckenstein doing a problem on the Y-Boulder in the Lake District that other excellent climbers could not do - to my mind this is evidence of a more sophisticated competitive environment, eclipsing the role of bouldering as merely training for the mountains. Eckenstein may well have been the first true master of the sport : a climber who not only sets new standards of difficulty, but contributes in a substantial way to the evolving philosophy and practice of bouldering. In Scotland - during the 1880s - Fraser Campbell and others engaged in a light-hearted training activity they described as "boulder climbing". However, the vast majority of British climbers declined to recognize bouldering as a legitimate sport in itself until recent times, unlike the French rock aces of the years between the World Wars - who began to explore the separation of bouldering from traditional climbing. A Departure from Tradition

Pierre Allain and his crew popularized climbing on the giant boulders in France's Fontainebleau in the 1930s and, later, after the War, in the1940s, asserting that such climbing had intrinsic value in the Fontainebleau area - a major step on the European continent. They broke with the tradition relegating bouldering to merely training status - at Fontainebleau, but not elsewhere. The 'Bleausards performed elementary dynamic moves, used rosin for the feet, and started from small bouldering rugs. Clearly Allain deserves credit as an early master of the sport. In 1947 Fred Bernik designed the first circuits at Fontainebleau as training exercises for alpine climbing. British boulderers probably had practiced in a similar fashion wherever it was appropriate, but the French formalized the concept. Interestingly, it was at this approximate time (1941) that a climber established a 1,000 foot traverse along cliffs at Harrison Rocks, near London, popularizing such practice climbing on sandstone outcrops similar to those of Fontainebleau. The

Advent of Modern Bouldering

Perceiving climbing as an extension of gymnastics rather than hiking, I initiated a gymnastic approach to short rock climbs, specifically bouldering, in America in the 1950s. From the arena of formal gymnastics, I introduced chalk into rock climbing. Inspired by controlled releases and catches in artistic gymnastics, I began practising controlled dynamic moves, as a technique of choice as well as one of necessity, calling some "free aerials" (dynos). I also devised a preliminary and entirely separate bouldering grading system - useful in all bouldering environments. I may well have been the first serious climber to specialize in bouldering and to promote the "new" sport as a universal activity - not restricted to a particular locale - and to argue for its acceptance as a legitimate form of rock climbing. To many climbers this defines the beginning of modern bouldering. My 1969 article in the American Alpine Club Journal - The Art of Bouldering - encouraged the recognition of bouldering as an authentic form of climbing. There were several other American climbers of the 1960s who thought of bouldering as a legitimate and artistic climbing activity - including Rich Goldstone, the Colorado gymnast & climber, Pat Ament, and the Devils Lake genius, Pete Cleveland. By the mid 1970s a number of other climbers had begun focusing their energies on the small rocks. Using Sherman's V-scale - designed for use at Hueco Tanks in the 1990s - I would guess that the British achieved V0 to V1 levels around 1900. Allain and his companions probably reached V3 levels in the 1930s. And by the 1950s others at Fontainebleau had carried those levels up to V4 or V5. Although most of my problems by the late 1950s were V2 to V7, on occasion I did moves up through the V9 and V10 range, but probably not beyond that degree of difficulty. Jim Holloway likely reached V12 and above in the 1970s. He rarely dabbled with the easier stuff, and was one of the first to expend considerable time and effort - days and weeks - to work out particular moves. This attitude was a significant departure from boulderers of my generation. Prior to this time, even skilled climbers (including the author) spent at most a few hours working on individual problems - if that didn't suffice, we moved on to other challenges. Holloway, slim but graceful and powerful - and exceptionally tall - became one of the first focal points for an ongoing though somewhat casual dialogue about the influence of genetics on the classification of difficulty. The number of climbers performing at two-digit V-grades has increased significantly since that time. And difficulty levels have risen even higher. Additionally, the character of boulder problems has changed somewhat, with the latest requiring stamina as well as individual move abilities. At some point, toward the end of the 20th century, the occasional top-rope was abandoned by most boulderers in favor of the new bouldering mats. |

I

invite any viewer who has come across documented photographs and/or

written material, which conflict with any statement I have made on this

website concerning the origins of bouldering, to contact me. I seek

only the truth, and have no biases for or against particular countries

or personalities.

|

| In

the following pages, my preference is to allow climbers from the past

to tell us about their experiences. Where such quotes are not

available, I

narrate. I don't have a philosophical agenda. I only wish to show that

climbers have bouldered throughout the history of rock climbing (mostly

- but not entirely - as practice for longer routes) and

that the activity has gradually matured to the point that many in the

climbing community now accept bouldering as a legitimate climbing

specialty. Words, however, run a poor second to actual historic photographs . . . |

Early

British Boulderers

|

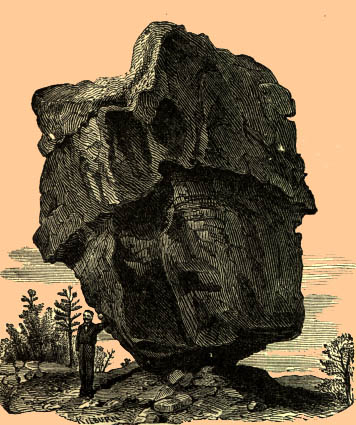

Bouldering is a historic and honorable sport! Photo British Mountaineering by Claude E. Benson, 1909 |

British climbers from the late 1800s coined the words bouldering and problem at approximately the same time they formulated and began developing the sport of rock climbing. It is likely that bouldering appeared initially as a rainy-day activity, when longer climbs were inappropriate, or as training in areas where larger rocks were not available, reflecting, as it did, the very short leads that were common when roped climbing was in its infancy. |

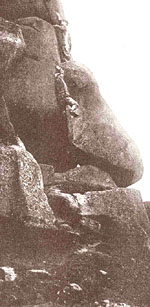

"Rock Gymnastics. The strain on the fingers is extremely severe. In fact the climb, as it is, approaches the limit of strength, and were it two feet longer I question whether it would not be beyond the powers of any man" - Benson commenting on the photo on the right. See the first bouldering shoes . Up through the 1940s, British boulderers could determine existing bouldering problems through the scratch marks on the rock left by these nailed boots. Within a few years after nails were abandoned, I saw to it that chalk marks would serve the same purpose! |

Photo British

Mountaineering by Claude E. Benson, 1909

|

|

Photos by George & Ashley Abraham |

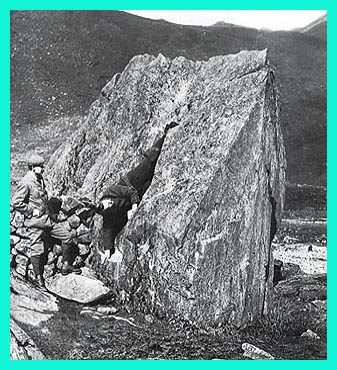

| In

this 1890s

photo Dr.

Joseph Collier (1855-1905), a leading Manchester

surgeon, is seen climbing the Y

Boulder in Mosedale using the required

technique: upside-down! Watching him is his companion, A. E. Field. Collier was an all-round athlete who had engaged in rugby, tennis, golf, and cycling. He was tall, but agile, and had an exceptional reach. A mountaineer, he had climbed in the Alps and Caucasus before becoming active as a pioneer rock climber (and boulderer) in the English Lake District. |

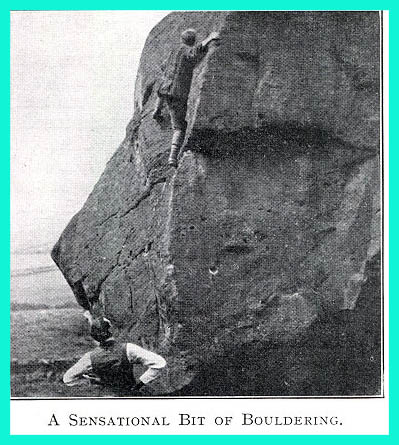

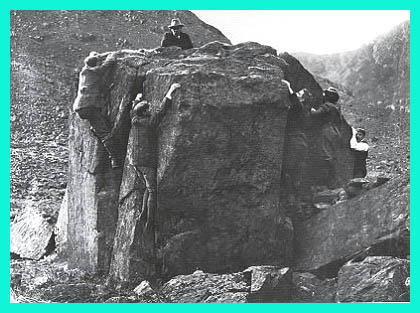

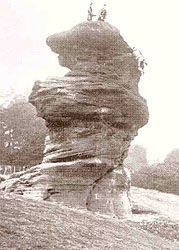

| 1890s: Six boulderers climbing simultaneously on the Bowderdale Boulder. Bouldering apparel included Norfolk jackets, knickers, and nailed boots. One of the athletes seen here is a woman. |  Photo by George & Ashley Abraham |

|

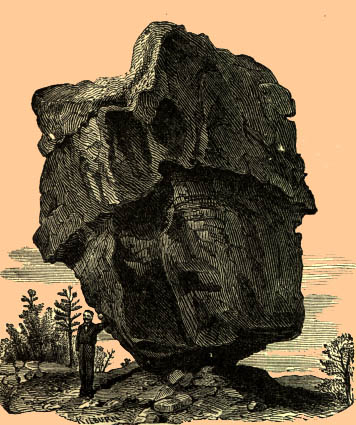

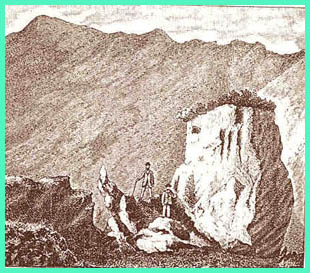

Here is a drawing, done from a photo by A. Pettit, showing early climbers at Gash Rock, in the 1870s. One of these gentlemen, Colonel John Barrow, wrote: "This is a conspicuous rock on the left of the pass, standing on a steep eminence, and is some 30 feet high with a flat top covered with heather and two stunted ash-trees. It is perfectly accessible on all sides, and could only be mounted by a rope or ladder." He further adds, that since it has no name, he will give it the name of his guide. W. P. Haskett Smith in 1894 comments that: "We are indebted to Colonel Barrow for this name, which he bestowed on Blea Crag . . . for no better reason than that he knew a man called Gash, who did not know the name of the rock, or how to climb it." .

. .

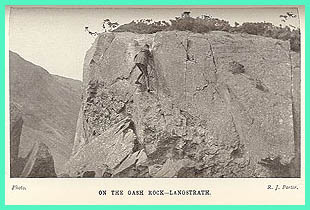

Here's a photo of Gash Rock, taken 1900-1910, showing a lone boulderer. There is a rumor that Owen Glynne Jones - one of the first truly athletic climbers - did an early highball problem on Gash Rock. Photo J. of Fell & R. Climbing Club/ Courtesy Henry S. Hall, Jr. American Alpine Club Library |

|

An Early Bouldering Session . . . The following is a passage from British Mountaineering, by Claude E. Benson, in which the author describes a solitary bouldering session, prior to 1909 : ". . . but even a solitary boulder is by no means to be despised. I experimented on such an one the other day . . . It was not more than ten feet high, and in shape somewhat resembled a penny bun. I found seven different ways up, all affording genuine climbing, and two or three other problems which proved too much - for me, at any rate. By the time I had done with that boulder I was feeling wonderfully fresh and fit. . . . Now a man with a boulder like that in the neighborhood ought to be able to keep in fairly good form."

Just a Boulderer . . . Again, from Benson : "An hour's practice . . . will do more to get your climbing muscles in order than many of the recognized moderate courses. . . . you put in twice as much work and that work is two or three times as difficult. It is extremely hard to convince some climbers of this. They must go off and do something big, and megalomania bears them away captive . . . Nevertheless, if one can do so, one will be more than repaid by bouldering." |

|

|

|

| Photos

from left to right, above: J. Croft (1898), G.A. Fowkes (1900), G.A. Fowkes (1900) |

|

|

|

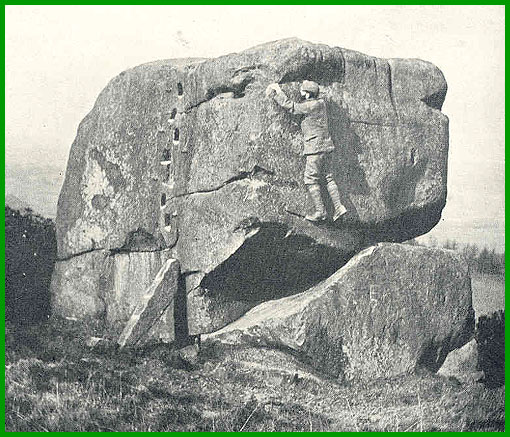

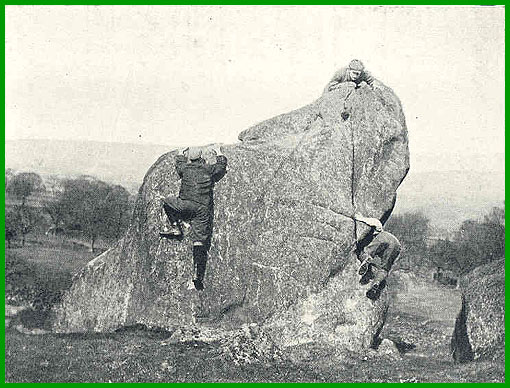

| From left to right: The Boulder at Robin Hood's Stride (Photo by Bird & Co., Stamford , 1898), Stonnis Crack, Black Rocks, Cromford (photo by G. A. Fowkes, ca 1900), The Hemlock Stone (photo by G.A. Fowkes, ca 1900). |

Photo G.

A. Fowkes,

courtesy of Henry S. Hall, Jr. Amer.Alpine

Club Library

From the Climbers Club Journal, Volume 5, 1903. |

The

Andle Stone :

The

inscription reads: "This

short climb

on the shoulder is exceptionally stiff. One has

to stand upright on one foot holding by a single nail

to the edge of a tiny crack, while the hands are spread against the

sheer face above. Making a long stride in this way, the climber obtains

a sufficient grip on the top corner, and pulls himself up easily." |

Comments: This is photographic proof that eliminate problems existed in the earliest years of bouldering.The climber on the left might possibly be Oscar Eckenstein (see the next page). Photo G. A. Fowkes, courtesy of Henry S. Hall, Jr. Amer.Alpine Club Library From the Climbers Club Journal, Volume 5, 1903 |

An Unknown

Boulder : The inscription reads: "Two problems. There is a third in between, and one or two others behind the rock, all trying. The man sprawling on the narrow ledge at the corner has got there simply by using his hands, and without utilising a certain step underneath that would make the whole thing easy. He has now to stand upright against the overhanging top of the boulder and pull himself up." |

| The

Wharncliffe Boulders In the Climbers Club Journal, Volume 4, 1902, C. F. Cameron, at the end of an article on the Wharncliffe Crags, has this to say: "This article would be incomplete without reference to the boulders. In no part of England is there to be found a better variety of boulder problems than among the huge detached fragments of rock that lie in confusion at the base of Wharncliffe Crags. The resources of the locality in boulders have not yet been exhausted; but climbs have been attempted on some twenty boulders, several of which present three or four problems each. Half a dozen of these climbs are stated by experts to be absolutely first class as boulders go. A hard-working afternoon may readily be spent on boulders alone." |

Contrived Problems

In Moors, Crags, and Caves of the High Peaks (1903), E. A Baker has the following to say about contrived problems: " Our Sheffield hosts are in the habit - from strictly scientific motives, of course - of eliminating the more convenient holds from any given climb, much in the way a crafty examiner leaves out the handiest logarithms; and so they can set the newcomer some particularly severe exercises. A certain face climb, for instance, was stiffened by the imaginary removal of a large boulder; and it was gratifying to the Sheffielders to see how regularly their guests dropped off on the rope as, one by one, they reached the level of this desirable stone." |

Chipped Holds

Elsewhere, Baker (1903) speaks of climbing a rock with carvings on it: "Every precaution will, of course, be taken by the punctilious scrambler to avoid making use, as finger-holds, of the initials, names, and flourishes that have been incised on the rock by that part of mankind which never climbs without leaving its mark. Should you inadvertently lay hands on one of these or use it as a toe-scrapper, it is incumbent on you to descend and make a fresh start." The thoughts here expressed are in marked contrast to the Fontainebleau practice of chipping holds that endured until the 1980s. |

| Page 2 | Oscar Eckenstein |

| Page 3 | Archer Thomson , Crowley, O. G. Jones |

| Page 3.1 | Aleister Crowley's 1898 Bouldering Guide |

| Page 3.2 | Gash Rock First Ascent 1893 |

| Page 4 | British Bouldering (continued) |

| Page 5 | Joe Brown Conversation |

| Page 5.1 | Early Scottish Bouldering |

| Page 6 | French & Australian Bouldering |

| Page 6.1 | German & Italian Bouldering |

| Page 7 | American Bouldering 1 |

| Page 8 | American Bouldering 2 |