www.johngill.net

|

|

| Commentary & Reflections 1953 - 2007 |

|

|

| Commentary & Reflections 1953 - 2007 |

North Georgia 1953 Photo John Gill, Sr. |

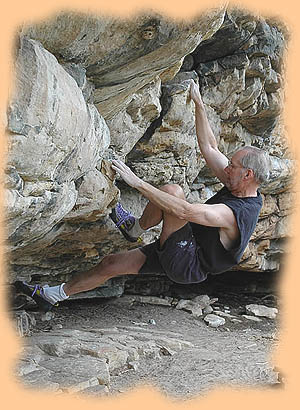

Little Owl Canyon 2005 Photo Eric Hõrst |

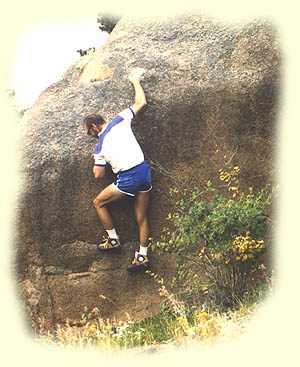

Topping out on a highball, 1997 Photo Pat Ament |

"This

is a tale of a first encounter - stereotyped perhaps, but quite real

nevertheless - with John Gill . . . Mr.

Gill was a tall person, quiet and not particularly impressive as long

as he stood absolutely still! - Paul

Mayrose in

Master

of Rock "He could be the guy standing next to you in line at the supermarket . . ." - Curt Shannon in Master of Rock "

. . . In John I saw a man more relaxed and at ease than I would have

thought fitting for a climber of his reputation. He did moves simply

because they pleased him. It did not matter their worth to anyone else.

John and I had contrasting styles and it was good thing. It allowed us

to climb together comfortably." - Bob

Williams in

an interview on |

| Page 1 -

The

1950s |

| A Trip out

West. Gymnastics. Stone Mountain. Climbing+Gymnastics.

Introduction of Chalk & Modern Dynamics. Bouldering -The First

Specialist? |

| Page 1.1 | Bodyweight Feats & Gymnastics: Alternatives to Climbing |

| Page 2 | A Golden Age. Bouldering Ratings. Aging Boulderer. Meaning? |

| Page 3 | Bouldering, Kinesthetics, Dynamics. Early V9. |

| Page 3.1 | Ethereal Bouldering . . . No-Hands Problems. Bob Kamps. |

| Page 4 | Bouldering in Photos. My Bouldering Companions. |

| Page 5 | Early Attitudes. Pads & Ropes. Top Ropes. Buildering. Slacklining. |

| Page 6 | Occasional Hard Problem. Traditional Roots. Climbers Campground. |

| Page 7 | Soloing. Thimble. Injuries & Old Age. |

| Page 8 | Interviews & Profiles. Climbing Writings. Links.Citations. Warning. |

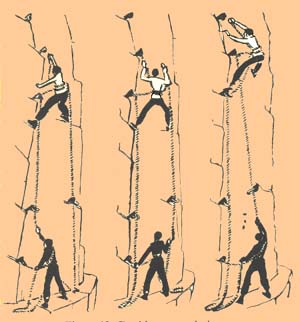

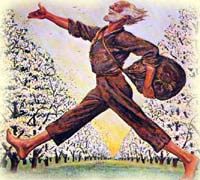

I942 Handbook of American Mountaineering

Illustrations

by Virginia Lee Burton

|

|

|

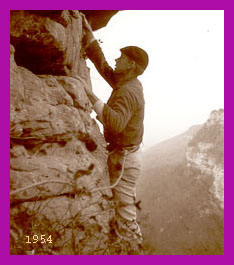

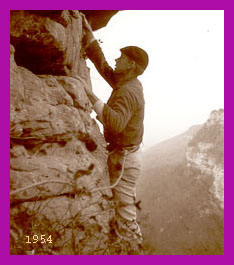

A Trip Out West . . . A Scramble on a Mountain Wall . . .  I started climbing in 1953 while on a

day-trip to north Georgia - an amateur archeological outing.

My first climbing rope was manilla fiber and my first climbing shoes

were work boots I bought from Sears and took to a cobbler to have red

rubber Vibram soles attached. I started climbing in 1953 while on a

day-trip to north Georgia - an amateur archeological outing.

My first climbing rope was manilla fiber and my first climbing shoes

were work boots I bought from Sears and took to a cobbler to have red

rubber Vibram soles attached. Fort Mountain in north Georgia, 1954 After graduating from high school in 1954 a friend, Dick Wimer, and I drove out to Colorado that August in his 1936 Ford convertible - with mechanical brakes. The freeways had not been built yet, so this was a more adventurous road trip than it is now.  We camped in Meeker Park below the slopes of

Mt. Meeker, a 13,000 foot mountain adjoining Longs Peak. We camped in Meeker Park below the slopes of

Mt. Meeker, a 13,000 foot mountain adjoining Longs Peak. Dick

Wimer & Dave Lewis

at Maroon Lake 1954

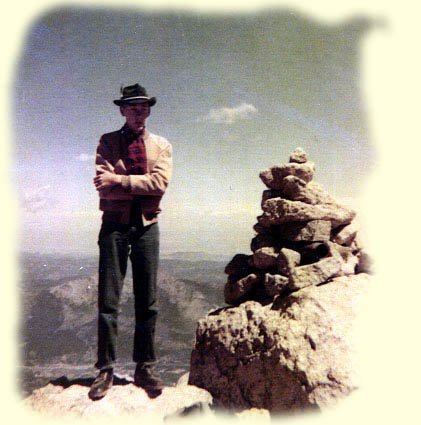

I had looked forward to climbing the east face of Longs, but once in Colorado Dick confessed he didn't want to go back up on the wall, where he had broken his leg the previous summer. So, I sneaked out of our pup tent early one morning, caught a ride to the Long's Peak Ranger Station, and hiked up to Chasm Lake, at the base of the east face. I had a short length of rope with me, an ice ax, and a few pitons and carabiners. And I wore my J. C. Higgins' work boots.  I picked out a line

running up the steep Mill's glacier buttress and innocently set out to

climb it. I made rapid progress until I

encountered a blank spot. With little regard for style (what was

that?) I tossed a loop of rope over a high knob and pulled myself up

hand over hand. I picked out a line

running up the steep Mill's glacier buttress and innocently set out to

climb it. I made rapid progress until I

encountered a blank spot. With little regard for style (what was

that?) I tossed a loop of rope over a high knob and pulled myself up

hand over hand. Longs Peak 1954 Photo Al Hazel Reaching the top the buttress, I crossed the ice to Broadway Ledge. There I was met by a guide (Al Hazel - RIP June 30, 2005). He had hiked up to replace the summit register, and had been requested by the Longs Peak Ranger to check on me after Dick had divulged my plans. I wasn't the crazy teenager he had been led to believe, and we continued up the Little Notch to the top. We descended very slowly, for Al had trouble with a trick- knee, and when we were a short distance from the ranger cabin, Al told me to wait there while he talked to Bob Frossen, who was ready to string me up by my ears but was mollified somewhat my Al's entreaties on my behalf. What a great adventure for a kid from the Deep South with no athletic background and virtually no climbing experience! .

. .

We climbed several formations in the Flatirons, including the Maiden, with its thrilling 120-foot rappel. Even as early as 1954 this climb was becoming the sort of adventure you took your girlfriend on. There were several routes to the top, including Dale Johnson's recent aid climb of the northwestern overhang. The Maiden is a spectacular hooded cobra when viewed from the west. A few days prior to our Flatiron's visit I had managed to get my new high school graduation ring stuck in a crack on Horsetooth Rock, below Mount Meeker. I almost lost a finger, and rarely have worn rings since. Dick and I made a first ascent of a tiny spire on the Crags, near Twin Sisters. It must have been 5.7 with a piton or two for protection, but finding it and getting up it first was a real thrill. At 17 I was ridiculously naive, but that made everything exciting. We climbed a number of Colorado peaks, including the old cable's route on Longs and the north side of the North Maroon Bell, and did a few more short rock climbs before pointing Dick's car to the east for a return to Georgia where we both had enrolled for the Fall Semester as freshmen at Georgia Tech. |

My

First Visit to the Black Hills' Needles & the Tetons . . .

The following year

(1955), my parents and I took a road trip through

the west, stopping in the Black Hills, where I climbed

my first Needles' spire, a short 4th class tower of knobby granite. We

also spent a few days in the Tetons, where I joined several members of

the Princeton Mountaineering Club for an ascent of Teewinot.

This Wyoming mountain range - so much more spectacular than the

Colorado Rockies - fascinated me, and I vowed to return each summer

while I attended college. We stopped in Rocky Mountain National Park,

and I soloed a few small, easy formations below McGreggor, a giant

dome near the east entrance. Gazing up at its granite slabs, I promised

myself I'd come back and climb it. (in the Spring of 1962 I soloed

a route more or less up the center). I also did some light bouldering

in the Park - unaware of even the name of the craft. The following year

(1955), my parents and I took a road trip through

the west, stopping in the Black Hills, where I climbed

my first Needles' spire, a short 4th class tower of knobby granite. We

also spent a few days in the Tetons, where I joined several members of

the Princeton Mountaineering Club for an ascent of Teewinot.

This Wyoming mountain range - so much more spectacular than the

Colorado Rockies - fascinated me, and I vowed to return each summer

while I attended college. We stopped in Rocky Mountain National Park,

and I soloed a few small, easy formations below McGreggor, a giant

dome near the east entrance. Gazing up at its granite slabs, I promised

myself I'd come back and climb it. (in the Spring of 1962 I soloed

a route more or less up the center). I also did some light bouldering

in the Park - unaware of even the name of the craft.On top an easy spire in the Needles of South

Dakota 1955

Photo J. Gill, Sr. |

Gymnastics

. . .

My Eyes are Opened . . .

In the Fall of 1954 I enrolled at Georgia

Tech in Atlanta, planning to major in physics.

All freshmen had to take a quarter of gymnastics, a sport I knew

nothing about. I had never been athletic, nevertheless I found

gymnastics fascinating, and surprised myself by

getting an "A" from the instructor, the men's gym team coach, Lyle Welser. In the Fall of 1954 I enrolled at Georgia

Tech in Atlanta, planning to major in physics.

All freshmen had to take a quarter of gymnastics, a sport I knew

nothing about. I had never been athletic, nevertheless I found

gymnastics fascinating, and surprised myself by

getting an "A" from the instructor, the men's gym team coach, Lyle Welser.

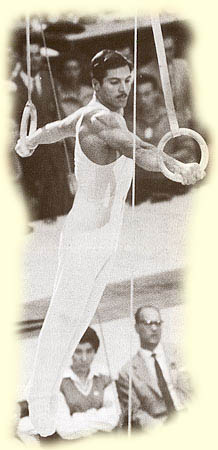

A rope or pole climber in 1826 I wasn't all that strong, but I did seem to have a natural pulling ability, and, after the course was over, started practicing the 20' rope climb with a couple of team members. This was a challenging gymnastic event, with the first modern international competition having taken place in 1896. It wasn't popular with artistic gymnasts, however, and timing the climb presented a problem. Consequently rope climbing for speed was discontinued in 1963. The

other piece of traditional gym apparatus that attracted me was the Still Rings,

although it would take a couple of years' work to achieve any real

mastery.

One immediate consequence of my introduction to gymnastics in the fall of 1954 was to adopt the use of chalk in rock climbing and buildering activities - a simple innovation that, once introduced to fellow climbers, evoked a more athletic view of rock climbing. |

1955 Bill Taylor & Me  |

Cloudland

Canyon

Here's

a

photo of Bobby

Mitchell doing a Tyrolean traverse in Cloudland Canyon

in

1955. Cloudland Canyon, in northern Georgia, was a

moonshining area at that time. In the early morning hours you might see

a wisp or two of smoke rising from the wooded valley. If you put five

dollars in a bucket and lowered it on a rope over the cliff into the

forest, after a while you might feel a tug, and pulling the bucket up

would reveal a bottle of pretty good hooch.

I remember rapidly scampering up a chimney to the top of the cliffs one day when I detected what appeared to be an armed sentry making his way toward me through the dense undergrowth. |

Physique

. . .

What is Desirable?

Over the next couple of years as I worked the still rings and rope and climbed more, I went from a gangly and ineffective 145 pounds to about 180, all added muscle. By 1956 I had became an athlete, although at a muscular 6'2" I was a bit large for gymnastic rock climbing - or gymnastics. (Craig Luebben once referred to me in print as "looking more like a lumberjack than a modern rock climber"). It's ironic that nowadays one might want to trim down to 145 in order to hang on the smallest holds! Bob Murray, the great Southwest boulderer from the late 1970s and early 1980s was my height. According to John Sherman: "Murray peaked in 1984, packing on 15 pounds of muscle. Still, he was more beanpole than beefcake; at 6'2"he weighed a scant 150 pounds . . . a Saran wrap coating of skin over the muscles".

Handstands 1957,

Front Lever 1962 - click to enlarge

Had I forseen that, many

years later, the mantra would be

"the thinner the better", I might not have been quite as enthusiastic

about rock climbing - for gymnastics and climbing were, at least

partly, vehicles to carry me toward an

image of manhood in which physique, athletic ability, and intellect

were in balance. Here are a few

gymnastic snapshots taken in my backyard in 1957, showing

various handstands , a straight body

press to handstand , an L-position , and

a front lever .

|

Perceiving Climbing as Gymnastics . . . My Paradigm of Climbing+Gymnastics The

Standardization of Competitive Gymnastics . . .

The early to mid 1950s was a major transitional period in international gymnastics. Although the sport had been around since before the 1896 Olympics, attempts at standardizing equipment, events, and judging criteria had not been entirely successful. For example, prior to 1952 women competed on the men's parallel bars. Soviet gymnasts, who had labored for years in relative secrecy, came onto the scene in the 1952 Olympics with an impact that shook the athletic world. They exhibited, for MovieTone News and the new medium of television, gymnastic routines of unprecedented difficulty, grace, and precision - astounding viewers and spectators in a global arena. What had been a minor and unheralded sport - unsure of its status - became an athletic enterprise of some consequence. Azaryan

. . .

Early

on, I had seen a potential connection between rock climbing and the

dynamical and strength moves of formal gymnastics. This became an

incontestable conviction when I happened to see a movie newsreel of the

great Armenian gymnast Albert

Azaryan performing on the Still Rings.

Azaryan won the gold in two Olympics, and the story of his rise from

humble village blacksmith to Olympic Still Rings champion is chronicled

in the film

Rings of Glory , in which he portrayed

himself. I was riveted by his performance, and immediately set a goal

for myself of duplicating much of what I had seen - as an amateur

gymnast. Early

on, I had seen a potential connection between rock climbing and the

dynamical and strength moves of formal gymnastics. This became an

incontestable conviction when I happened to see a movie newsreel of the

great Armenian gymnast Albert

Azaryan performing on the Still Rings.

Azaryan won the gold in two Olympics, and the story of his rise from

humble village blacksmith to Olympic Still Rings champion is chronicled

in the film

Rings of Glory , in which he portrayed

himself. I was riveted by his performance, and immediately set a goal

for myself of duplicating much of what I had seen - as an amateur

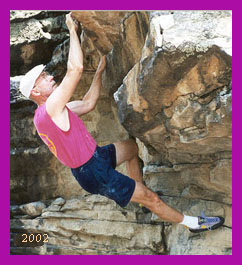

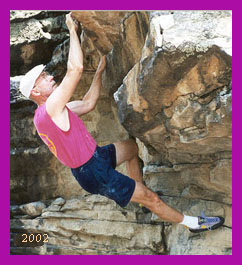

gymnast.Albert Azaryan. Photo by Alan Burrows, 1960 Click Developing, over several years, that kind of power, strength, controlled dynamism, and finesse on the rings was a rewarding experience, and applying it to the rock boosted my technical abilities and introduced an element of grace through strength that generated - at least to me - the perception of climbing as a kinetic art. Of course, I never came remotely close to the performance level of Azaryan - only in my dreams! It was during this time, as I became aware of the potential artistic gymnastics implied for rock climbing, that I began to see the latter less as an extreme form of hiking, and more as a genuine athletic event - a brother to gymnastics rather than a second cousin. My

Gymnastic Philosophy of Climbing

By the mid to latter 1950s I was convinced that rock climbing should be perceived as an extension of gymnastics, rather than as an extension of hiking , which was the prevailing view. The Sierra Decimal System was well established by then, and clearly reflected the hiking paradigm: Class 1 was walking, Class 2 was steep hiking, Class 3 was scrambling, Class 4 was climbing with exposure and a rope, Class 5 was what we now call "trad climbing", and Class 6 was climbing with artificial aid. To break with this perception, I began to focus on very short climbs on boulders and small outcrops, treating rocks as a gymnast would treat his apparatus. I also began, informally, to grade these problems on a numerical personal scale (1, 2, and 3) - similar to the existing gymnastic scale of difficulty (A, B, and C). Later I refined this to the old three level B-Scale for bouldering, assuming that the gymnastic scale would remain three-tiered, with moves shifting on the scale as greater difficulty emerged (a C move would become B, etc). B-3's were to designate a problem so difficult it had been done only once - on a personal level this would be the hardest thing I could do. Nowadays, the gymnastic difficulty scale is A, B, C, D, and E - essentially open-ended. There are even Super-E moves. Will they become F moves? The bouldering scale due to John Sherman is V0 through at least V15, with no end in sight. However, a personal three-level scale works quite well for boulderers who are more concerned with personal progress than with competition. Jim Holloway and Klem Loskot have used such a device. Chalk and Gymnastic Dynamics . . . The use of momentum in gymnastics provided a key for a controlled dynamical approach to climbing. It seemed perfectly reasonable to me that rock climbing - as a kind of gymnastic activity, rather than an extension of hiking - should have a substantial dynamic component. Simple jumps and "lunges" had been done for years - but difficult skilled and precise gymnastic "releases" upon rock required greater strength, more effort, and more practice. The age of the dyno had arrived (although the word itself didn't appear until the late 1970s). The serious use of momentum became a choice of style, and not simply a desperate technique of last resort. And no gymnast would work on challenging releases without chalk - neither should a climber. |

|

Introduction of Chalk and Dynamic Style into the Larger World of Climbing . . . In the mid 1950s, while visiting the Tetons, a mountaineering destination for Americans (including some top Yosemite climbers) and Europeans at that time, I introduced the use of chalk into the larger climbing community. I emphasized its value in particular for my concept of controlled dynamic style on boulder routes. When I demonstrated the efficacy of chalk - which I had bought at the Jackson Pharmacy - most climbers were instantly seduced, although some purists initially rejected it as unethical (Chouinard had qualms). The use of chalk quickly spread to Yosemite and to the east coast. In 1958 I brought chalk to Devils Lake - which made a substantial difference on the warm, slippery quartzite. The next few years saw the use of chalk spread throughout the world climbing community. Dynamics took a bit longer to gain acceptance, to some extent because of lingering effects of the US Army policies regarding three-point suspension and the British attitude toward control and fall-avoidance. Twenty years earlier, climbers at Fontainebleau had jumped for initial holds on some boulder problems, but what I encouraged was a far more controlled use of momentum that focused on dead-point maneuvers of various kinds, including free-aerials (now called dynos). |

It's Called Bouldering . . .

From Yvon Chouinard, I learned - in the mid 1950s - that what I was doing was called bouldering, a lighthearted conditioning pastime enjoyed by several of the top California climbers of that period at places like Stoney Point near Los Angeles. .

. .

.

. .

The First Climber to

Specialize in Bouldering . . . ?

Considering it an ideal application of gymnastics to climbing, I became quite possibly the first (and for some time, only) climber of any consequence to primarily focus his efforts on bouldering, both participating in the sport and promoting it as a genuinely worthwhile specialty. Like Johnny Appleseed, I traveled, planting the seeds of bouldering in several areas in the south and the west and encouraging the sport where it had taken root. Now, fifty years later, I'm able to assess and relate how my activities fit in the chronology of an athletic craft that is international in scope and over one hundred and twenty years old. As it turns out, my predecessors in bouldering history, the early advocates of the sport - Oscar Eckenstein (British -1890s) and Pierre Allain (French -1930s) - were, foremost, alpinists and rock climbers who, in addition, valued bouldering and accorded it some measure of status above that of a training exercise. Many others - throughout the history of rock climbing - found bouldering to be somewhat effective as preparation for longer climbs, or saw it as a light-hearted divertissement - but failed to perceive (and thus support) it as a legitimate and independent activity. Times change, however . . . |

Thirty-three Years as A Boulderer

& Fifty-three Years as a Climber  Just

one more reach .

. . didn't make it!

In the Wet Mountains, 1987 Shortly before an injury expedited my withdrawal from bouldering Photo

Chris Jones

|