| A Golden Age of American

Bouldering Reactions & Ratings Aging Boulderers Adults & Children Meaning of Bouldering |

|

|

Reflections

& Commentary: Page 2

|

| A Golden Age of American

Bouldering Reactions & Ratings Aging Boulderers Adults & Children Meaning of Bouldering |

|

Fenton's Corner, Estes Park, ca. 1963 |

The Scab, Needles SD 1963 |

Bouldering

takes Form . . .

During the late 1950s through the 1960s new, hard bouldering routes were done by Ament, Robbins, Kamps, Cleveland, Goldstone, myself, and a number of others. I became fairly serious about this "new" sport, and acted as its principal advocate and promoter during this period. Usually (but not always), problems from this era could be done by a competent boulderer on the first or second visit, although occasionally they may have taken a bit longer to initially work out. Generally, difficulty levels were such that unusual physical traits were not required - merely persistence and some degree of training and dedication. Most boulderers were also traditional climbers. I had devised a personal, three-level rating scheme that some other climbers used as well. Its simplicity frustrated controversy. This was an era of exploration and initiation, although competitive spirits were rising as climbers sought to discover their personal technical limits. The 1960s were a transitionary period when "Can I get up this section of rock?" gradually gave way to "How hard a problem can I do?" |

Royal bouldering at Makanda Bluff, 1973 Photo Gary Schaecher in Vertical Heartland (2005)  Bob Kamps bouldering in the Black Hills, early 1970s  Mark Powell, 1960s |

Reactions Toward My Bouldering . . . Climbers of the Golden Age of American Climbing who Bouldered . . . "Ever wanted to make an outrageous assertion and get away with it? Just pick the blankest side of a boulder or the most ridiculous looking overhang and say that a few years ago you saw John Gill walk by and climb it" - Steve Wunsch in Master of Rock When I began to do less roped climbing and more bouldering in the late 1950s, there were those climbers who thought my choice of a specialty was odd. Normally, they weren't rude, but simply let it be known that they were going out to do a real climb. What I found interesting was the fact that those climbers I knew who were in the very top ranks were more understanding. Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, Bob Kamps, Dave Rearick, Mark Powell and others were, in fact, enthusiastic boulderers, and while they were more interested in the longer routes – this was the Golden Age after all, and there was much to be done! – they thoroughly enjoyed bouldering sessions. Royal, whose very name positioned him accurately in the hierarchy of climbing talent, was very competitive in all areas of the sport, and was a serious and excellent boulderer.( Royal & me - 1991 ). Bob Kamps , whose face climbing skills were unsurpassed, was a delightful and challenging bouldering companion, and took those efforts seriously, as did his frequent climbing partner, the academic mathematician and amateur gymnast, Dave Rearick. ( Here are two photos of Bob & Dave (courtesy B. Kamps) after their FA of the Diamond in 1960, and in 1992). Dave and I used to press handstands on the cement slab of the Climbers' Campground in the Tetons. Later, in the mid 1960s, Pete Cleveland and I bouldered together and climbed together on several occasions, and this superlative climber was a tremendous and focused bouldering competitor. The Californians had polished their skills at Stoney Point, before launching a new era of bouldering in Yosemite, and Pete had done his preliminaries at Devils Lake (which, because of its topography, certainly encouraged the spirit of bouldering). Mark Powell (courtesy B.Kamps) once told me that even though I had acquired certain physical abilities that several of the West Coasters found a a bit provocative, they were friendly towards me because they felt that by focusing on bouldering I presented no direct threat in those areas of climbing they considered most important. Some were dismissive, but others perceived that bouldering might have a sort of peculiar potential, and were energetic boulderers. So, even though there were very few dedicated boulderers, the social climate among climbers was untainted by any sort of overt collective disparagement of my specialty. Modern Bouldering . . . My Interpretation It seemed to me the stage was set for the decisive emergence of a new, gymnastic, more dynamic form of bouldering, a specialty that would press beyond existing roped standards - which, in America, by the end of the 1950s, were just beginning to exceed 5.9. What seemed harder than 5.9 became "5.10", and there were very few of these. (Although in Utah in 1949, Harold Goodro had done the first American 5.10, calling it 5.9 - the top of the existing scale). By using new training techniques and more dynamic motion, however, I was able to do short pitches or boulder problems - by 1958 and 1959 - that would today be rated 5.12 to hard 5.13 (V9 - V10) - but were then simply 'more difficult' than the new 5.10s. To reflect this reality a new and specialized grading structure would be helpful. |

The Ripper at 50, 1987: B1, V5, 5.12c, 7b+, 6b, 27, 9, VI.4+, Xa, VI, 8, 8c, E5 |

|

In 1958 I devised the

first American bouldering rating

system . At

that time "trad" climbing was king, and had there been any forays into

what we now call "sport" climbing, they would have been dismissed as

unethical. Consequently, as Yvon Chouinard observed, " The

hardest moves will always be done on the boulders". I

envisioned three categories of technical difficulty:

B1 would denote the highest level of difficulty in traditional

roped-climbing, B2 would be a broad category of more difficult or

"bouldering level" problems, and B3 would be an objective category

signifying climbs

that were unrepeated, though attempted. When a B3 was repeated it would

drop to a B2 or perhaps even a B1 level. As time went by, B1 would

correspond to higher levels of traditional climbing difficulty, and the

system would shift accordingly. My idea was to promote this new sport

by challenging climbers to improve their technical skills to the point

they were capable of "bouldering level" difficulty, but

discourage the degeneration of bouldering itself into a numbers-chase.

Unfortunately, my system was a bit too abstract and went against the

grain of normal competitive structures, where a simple open progression

of numbers or letters signifies progress. For a while, I was virtually

the only climber in America who thought of bouldering as a separate,

self-contained climbing activity, and so the public rating format I had

conceived became more of a private convenience. And in that context it

worked quite well.

The concept of a three-tiered system has validity as a personal rating structure, but is woefully inadequate in an environment of mass competition. When Jim Holloway was at his peak, he used personal ratings referred to as JH(easy), JH(moderate), and JH(hard). Klem Loskot uses a personal system very much like mine, with B-1, B-2, and B-3 designations. In my personal interpretation of my B-system, I thought of B-1 as being difficult, but done fairly quickly, B-2 as very difficult, requiring a number of tries, and B-3 as the limit of my ability. |

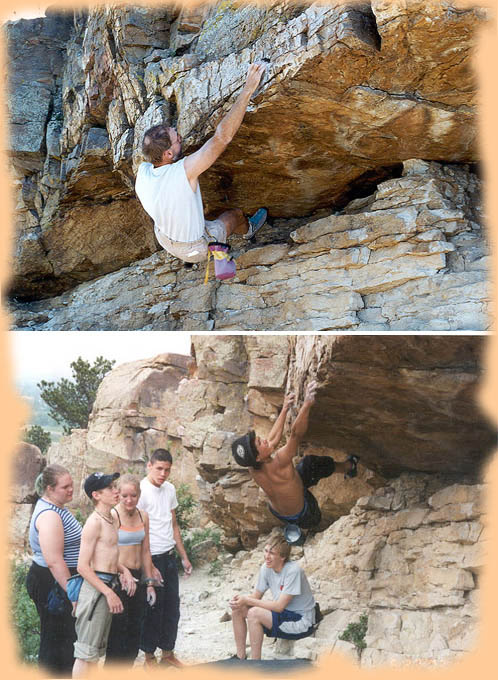

Adults and Children . . . Here is a photo of me bouldering at Horsetooth in May of 2003 with members of the Climbing Eagles of Adams County High School, coached by Todd Mayville. And here are shots of the crux portion of my old 1960s practice contrivance I called the True Torture Chamber. One of me at about 58, and the other of talented young Hector, 14 or 15, of the Climbing Eagles as he works out the sequence. The entire traverse runs about 5.13, I would guess. Children will always have a distinct advantage in making many rock gymnastic moves. In addition to the elfin lightness of youth, children have lymphatic systems that are superior to those of adults, allowing more continuous time on the rock surface before burning out. Tiny fingers make minute handholds seem large. |

"Let anyone of ordinary height take a friendly small boy of an active nature for practice on such a place [high stone wall at home . . .] and he will have the pleasure of seeing him easily climb up vertical places that are much more difficult, or probably impossible, for the taller man, even though he may be an expert mountaineer." - George Abraham in The Complete Mountaineer (1907) |