| Soloing First 5.12 / Modern Highball ? Mystical Aspects Injuries & Old Age Always an Amateur |

|

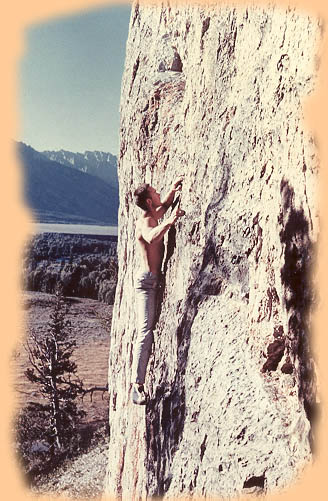

Blacktail Butte ca. 1959 |

| Soloing

. . . Although I had entered climbing in a traditional manner, I began to appreciate the freedom of spirit and continuity of motion possible by putting away the rope. Philosophically, I started thinking of myself as a "3rd class climber" - from the SDS nomenclature. I envisioned a climbing continuum beginning with bouldering, near the ground, and transitioning to what we now call free-soloing, as the space beneath my feet grew. In acknowledgment of the vastly increased danger of solitary climbing high up in the air, I usually soloed at modest difficulty levels, and focused on difficulty when close to the ground. Most of my soloing has been very conservative - much of it just exposed scrambling - but occasionally I have pushed myself into more taxing situations by collapsing the continuum. By 1960 I had free soloed the FAs of several difficult routes on Blacktail Butte in Grand Teton Park. ". . . John would usually drive over to Blacktail Butte for an hour or two of solo climbing. I never accompanied him there, and few people knew just what he was up to, but Bob Kamps went along once or twice and later told me he couldn't top-rope some of the things John was soloing" - Dave Rearick in Master of Rock. "Gill and I would go together to Blacktail Butte. It is grey limestone, absolutely 90 degrees, all finger holds. I remember the third route he did there. It may have been one of the first 5.10 routes in the country, because that was about 1959 or so. It's one of those things where you've got to go quickly and you've got to conserve strength. Your forearms get pumped up. Of course he didn't have to go fast, because his arms never gave out" - Yvon Chouinard in Master of Rock. I had also sneaked up onto several large formations in the Park at a time when soloing was illegal - such as the massive south buttress of Storm Point - to pick out and climb new lines. One afternoon I scrambled up to do the north face of Baxter's Pinnacle, and was surprised in the process by a party of climbing rangers. We were all embarrassed - but they were standup guys and didn’t report me! These were several exceptions to a more conservative soloing style. Between 1958 and 1962 I soloed many spires in the Needles of the Black Hills of South Dakota. Some of these were the first solo ascents. Sometimes I would take a rope with me and try to safeguard a hard move, but as time passed I put these protective devices aside. " . . . A trip to the Spire One area gave us our first glimpse of Gill. He was high up, alone on the spire. It was the first solo ascent of the route" - Paul Piana in Master of Rock |

K. Toshi on the Thimble, 1993 - Courtesy Iwa To Yuki |

| The

first 5.12 perhaps? . . . or the first modern highball? It's

one or the other . . . "Hats off to John Gill"

- Royal Robbins in the summit register on the Thimble

ca. 1965

My most demanding effort was the 1961 rope-unrehearsed, free-solo FA of a particular line on the thirty foot high Thimble Overhang in the Needles. At the time I was a junior USAF officer stationed at Glasgow AFB in northeastern Montana. I made a number of trips down to the Black Hills from Glasgow, roaring along the highway in my 1957 Studebaker Power Hawk (which tended to overheat). On a couple of these excursions I was accompanied by a young airman from the base who was interested in learning to climb. On several of these trips I ended my climbing day by bouldering on the lower part of my projected Thimble route - getting it wired - before I finally commited myself to the complete ascent. I had visualized this particular line while earlier climbing (essentially soloing) an easier route(5.9?) to the left of it, accompanied by Bill Woodruff. The obviously more severe route to the right became, in essence, a personal challenge to determine to what lengths I was willing to go as an exploratory solo climber. In retrospect it seems an insane aspiration and I am very lucky I didn't get wiped out in the process . However - and somewhat ironically - this ascent proved to be a turning point in the general recognition among the climbing community of my paradigm of bouldering - what has been called modern bouldering . Some see this as the first modern hi-ball problem, but to me it was a climb. ("When your feet are ten feet off the ground, you're climbing!" - Jim McCarthy, 1964, Tetons). At the time there was a wooden guardrail beneath the overhanging face, so that jumping off the upper half was no option. Even had it been, it would be thirty years before bouldering crashpads would appear. When I am asked

about its difficulty, I usually say that it seemed to be the hardest

free-solo first ascent I've ever done. However, I found I had

previously done boulder problems with moves on them quite a bit harder

than those I encountered on the Thimble. I'm told it goes at

a consensus V4 or 5.12a, maybe the first climb at that

level, but with the nature of the Needles' granite, it might seem a bit

easier or a bit harder to different climbers at different times, and

making a short traversing step to the left would certainly make it

easier. In the recent film, Friction

Addiction (2003), a very talented young boulderer takes a

long fall from the upper part of the problem. Pat Ament,

in his climbing history book

Wizards of Rock , says

"This was likely the hardest short free climb in the

world, at the time". During the 1970s

the late Kevin Bein worked out a top-rope route between my

route and the right edge of the overhang which was somewhat more

demanding.

Here is Pete Williamson in the mid 1960s at the start of my route on the Thimble . I understand that the 2nd ascent (in the style of the 1st) was done about 1987. It's not known precisely how many such ascents have been made - John Sherman made one in 1991, and in 1993 the Japanese climbers Kusano Toshi and Tsuge Motomu recorded a solo ascent on video that displays an elegance and grace I certainly never felt! But the Thimble is off the beaten track for contemporary boulderers, modest by current difficulty standards, and a little risky to boot, so you don't hear or see much about it these days. In addition, it's been climbed a number of times on top rope, which makes it a somewhat less attractive target for a serious modern climber/boulderer. That was it for me. I found my personal risk limits - and I didn't want to approach them again. After the Thimble I came to realize that the personal appeal of solitary climbing was, specifically, the continuity of motion and disinvolvment with equipment . So, from then on I usually avoided demanding lines and focused on scrambles and easy ascents when I got pretty far off the deck. |

| More recently, I have spent many hours on

easy granite towers near my southern Colorado home. "Looking across at the exposed corner, I decided I'd be ascending the easiest way I could find and would console myself by clinging with approximately twice the force that was actually needed to keep me attached. Not so for John. He climbed lightly and quickly, with complete confidence. He was always way up ahead of me, either happily entertaining himself with his selections or patiently waiting for me as I slowly and carefully made my way to his position." - Chris Jones, describing a solo adventure with me on Lover's Leap, in Master of Rock. |

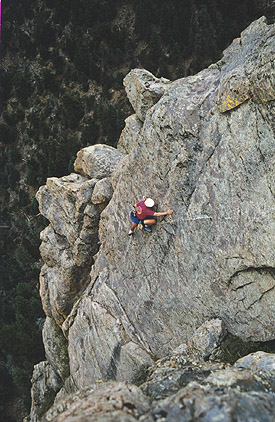

Soloing at Hardscrabble Pass, mid 1990s - photo by Heinz Zak |

Solo climbing is

an extreme form of

the sport and is clearly very dangerous. I never recommend it to anyone

| Mystical

Aspects . . . I began doing meditative practices in the late 1950s, mostly along the lines of Zen. Initially I was seeking a greater and more efficient command of my body and mind in order to advance my personal standards of difficulty. And, to some extent, this worked. However, I was surprised to find that a much greater gift had been bestowed: I was able to get more enjoyment out of the act of climbing - at any level of difficulty. As the years passed I spent more and more time repeating moderate and easy climbs, experiencing them as moving meditations , from which kinaesthetic awareness would evolve. I practised what Carlos Castaneda called "the Art of Dreaming", closely related to the modern concept of lucid dreams. The three-dimensional crystal clarity of objects perceived in this state fascinated me, and the ability to walk through solid objects was unforgetable. All this without recourse to any drugs . . . |

Don Quixote meets his nemesis . . . G. Roux, 1677 |

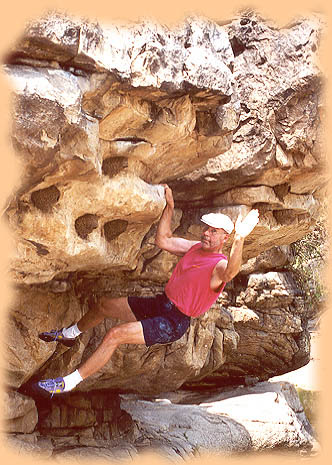

Injuries

& Old Age . . . I’ve had my share of injuries over the years, although nothing permanently debilitating. An early case of “climber’s elbow” about 1970 took me out of climbing for a year, and in 1987, when I was 50, I tore the right biceps off the forearm in a freak bouldering accident. After that I gave up dynamics and retired from any sort of competitive bouldering. But I'm still reasonably strong, although my shoulders are now severely arthritic and are a real problem, and I must be careful with my back . Bouldering in 2002 with the real master of rock, Peter Croft, at the Happy Boulders (photo by Jody Langford). Playing on an easy Red Rocks divertissement in 2003. |

From 2002 - the local rocks |

| There

Are Other Things in Life, besides Climbing . . . As a climber and boulderer, I always thought of myself as an amateur. I completed my formal education at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, chosen principally because of its proximity to Horsetooth Reservoir, which, in its pristine and virgin state, appeared to have the potential of becoming a world-class bouldering garden. I had a quite modest but satisfying career as a college professor and spent many enjoyable hours lost in mathematical thought, a pleasant complement to strenuous rock gymnastics. |

Photo by Bill Patterson, 2003 |