|

Origins of Bouldering |

|

Origins of Bouldering |

Archer

Thomson, Crowley,

Jones . . .

|

James

Merriman

Archer Thomson (1863-1913) : G. W. Young's

comments about the Eckenstein Boulder in Snowdon

Biography

actually end with

a reference to the practice of the sort of balance work promoted by

Eckenstein by one of the truly great pioneers of Welsh rock climbing

: "Archer Thomson

practiced with him [on

the boulders] , trim

and dark-clothed, with lion eyes and mane, and supple, silent

movements. He became by a short head the first practising master of

this conscious skill".

Professor Orton, in Thomson's obituary in the 1913 CCJ, makes the

somewhat cryptic statement: "He has

often acknowledged to the writer of these lines the debt he owed in

particular to one instructor [at Pen-Y-Gwryd]". This could

only have been Eckenstein, who was frequently on the sharp end

of establishment climbers' invective. James

Merriman

Archer Thomson (1863-1913) : G. W. Young's

comments about the Eckenstein Boulder in Snowdon

Biography

actually end with

a reference to the practice of the sort of balance work promoted by

Eckenstein by one of the truly great pioneers of Welsh rock climbing

: "Archer Thomson

practiced with him [on

the boulders] , trim

and dark-clothed, with lion eyes and mane, and supple, silent

movements. He became by a short head the first practising master of

this conscious skill".

Professor Orton, in Thomson's obituary in the 1913 CCJ, makes the

somewhat cryptic statement: "He has

often acknowledged to the writer of these lines the debt he owed in

particular to one instructor [at Pen-Y-Gwryd]". This could

only have been Eckenstein, who was frequently on the sharp end

of establishment climbers' invective. Through practice on boulders, as well as lead climbing, Young continues: "He evolved the somewhat specialized type of climbing which has been principally responsible for the extraordinary advance made in the standard of difficulty in recent years; the slow controlled movement, depending on a fine balance rather than a grip, and identical in pace and security upon easy crags or on the hardest passages." |

Thomson led his fellow

climbers out away from the

dark gullies, onto ridges and slabs,"where

the holds were as small as the sense of exposure was great".

(A. Hankinson, The

Mountain Men). He firmly believed in the principle of

climbing a pitch

from the ground up, avoiding the sort of top-rope practice before a

lead

that O. G. Jones employed, as well as the down-climbing of a route

before ascending it. He reasoned that to do either imposed a more difficult and dangerous task on the

second-ascent party. He

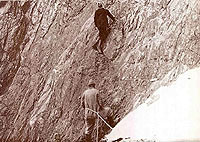

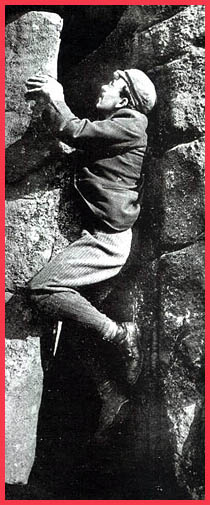

contemplated in an unhurried manner his next moves on a difficult pitch, "poised on nailholds high upon a steep slab, he would lean right back from his waist, mutely meditating upon the difficulties above for minutes together. . . leaning easily outwards, with half his body free, his feet and knees attached to the rock on some principle of balance all his own, and gazing upward with a smiling intentness that seemed half critical examination and half remote and contemplative pleasure." (G. W. Young). Eckenstein & Archer-Thomson at Lliwedd - by A. W. Andrews, circa 1903 |

Thomson went directly to

Wales from Cambridge in

1884.

In 1896 he was appointed Head Master of Llandudno County School, a post

he held until his death in 1913. At college he was Captain of the Football Club, and was on the lawn tennis squad. He was the best ice skater in North Wales, and once, when skating on a Sunday, incited the wrath of several quarrymen who considered his act a sacrilege. They actually began stoning him, but then dropped their stones and applauded Thomson, fascinated by his skill. He was reticent, and known to many of his comrades as a reclusive poet, rarely speaking but enjoying their companionship, nevertheless. Young comments: "For a number of us the cliffs of Snowdon . . . and the incomparable precipices of Lliwedd . . . will be haunted, and almost consecrated, by the memory of a figure, solitary and smoking, crouched on some picturesque and inaccessible shelf, or moving with extraordinary lightness of foot along the screes . . . ". Sadly, Archer Thomson was the first of the great British rock climbers to take his own life. |

Black

Magick . . . Black

Magick . . .

Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) - "The Great Beast 666" - was a fine rock climber and credible boulderer, as well as a free-solo advocate. Here is the way he describes himself: "Owing doubtless to my early ill-health, I never developed physical strength; but I was very light, and possessed elasticity and balance to an extraordinary degree". Photo The Confessions of Aleister Crowley Early experiences with inept guides turned him against any form of professional climbing, and he declared that the best amateurs were far superior to any guide. He was tutored in the basics of rock climbing by Norman Collie, the chemist who discovered neon and was the first to take medical X-rays. Collie was a major figure in early British climbing.  To

gain insight into bouldering

in the late 1800s, here are two of Crowley's descriptions

of separate incidents from that time period. One involves his

adversary Owen

Glynne Jones - a dynamic

climber who "leaped

for handholds" and practiced short, difficult routes on a

toprope before climbing them 'ethically' - the latter a procedure that

was controversial and considered cheating by some, as climbers had

begun debating the proper role of the rope as a protective device. Crowley, in addition, alludes to his own

predilection for rope-less climbing. To

gain insight into bouldering

in the late 1800s, here are two of Crowley's descriptions

of separate incidents from that time period. One involves his

adversary Owen

Glynne Jones - a dynamic

climber who "leaped

for handholds" and practiced short, difficult routes on a

toprope before climbing them 'ethically' - the latter a procedure that

was controversial and considered cheating by some, as climbers had

begun debating the proper role of the rope as a protective device. Crowley, in addition, alludes to his own

predilection for rope-less climbing.G. Grant

& Crowley at Beachy Head

[In the infancy of the sport of rock climbing (1880-1885) ropes had rarely been used in any capacity, and initial applications in the years that followed, seen in photos by the Abraham brothers, are chilling to behold. Haskett Smith, considered the father of British rock climbing, avoided the use of ropes or other protective devices in his early climbs, setting a precedent that others felt obligated to follow. Some think that his attitude arose from a casual approach to the new sport, but I suspect it was due rather to an attempt to lend credibility to an activity dismissed as inconsequential by older Victorian Alpinists.] The other incident perhaps set the precedent of sandbagging in bouldering, on a previously unclimbed boulder route in the Alps, with sad irony in the same area in which Jones met his death. This "wickedest man alive" was not without a sense of humor, however demeaning. Crowley Speaks . . . O. G. Jones & Early Sandbagging |

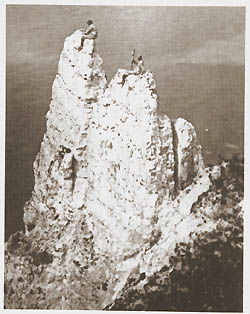

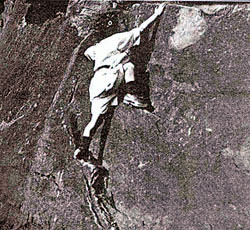

Owen

Glynne Jones (1867-1899), an early

gymnastic climber - some call the

first athletic rock climber - is seen here on Derbyshire

Gritstone. Probably the

first real "tiger", he devised a difficulty rating system that evolved

into the one used in Great Britain today. Jones, who began his short

but intense climbing career in 1888, had a strong

hand in establishing hard free-climbing as a proper end in itself,

rather

than merely as training for the Alps, although his tactics involving

the

use of the rope created some controversy. Owen

Glynne Jones (1867-1899), an early

gymnastic climber - some call the

first athletic rock climber - is seen here on Derbyshire

Gritstone. Probably the

first real "tiger", he devised a difficulty rating system that evolved

into the one used in Great Britain today. Jones, who began his short

but intense climbing career in 1888, had a strong

hand in establishing hard free-climbing as a proper end in itself,

rather

than merely as training for the Alps, although his tactics involving

the

use of the rope created some controversy. Nevertheless, it appears that he was climbing at the 5.7 and 5.8 levels, perhaps somewhat higher on boulders, in the mid 1890s. This should have put him at least on a par with free-climbing pioneers in the Elbsandstein area at that time, so that he could be considered one of the real forerunners of modern rock climbing. Photo Abraham Bros (1890s) As a young man, he showed both mechanical and mathematical aptitude, and at one point was an assistant in a mathematics department. With a first-class Honours degree in experimental physics, and unable to obtain a professorship, he became physics master at the City of London School. Never one to avoid recognition, he humorously referred to himself as "the Only Genuine Jones". He is described as having boundless energy and enthusiasm, and possessed an agreeable personality. It seems that everyone liked him - except Aleister Crowley. The following is a legendary story describing Jones' great gymnastic strength, related by the climber and photographer George Abraham, one of his staunchest supporters: "One Christmastime an ice axe was arranged as a horizontal bar . . . He [Jones] grasped the bar with three fingers of his left hand, lifted me with his right arm, and by sheer force of muscular strength raised his chin to the level of the bar three times." Fact or fiction? You decide. (When in my best physical condition, I was able to do a one-arm pull-up holding 20+ pounds in the other hand. I never pushed it further, but I suspect I might have been able to add another 10 pounds or so.) One might add here, that George Abraham was said to exaggerate at times, and even to tilt his camera to make a climbing shot more impressive! To put this suspect claim in proper context, go to another section of this website: In Climbing Days (1935), the author, Dorothy Pilley, speaks of Jones' rumored feats: ". . . Owen Glynne Jones, hero of innumerable unemulatable acrobatic feats.. . .That he could pull himself up on the top of a door ten times by the tips only of those slim fingers . . . I had known for years.. . But that he could make a standing jump in climbing boots from one platform to another across a single line of rails was a new and wonderful item of information." Jones was fondly referred to by his many friends as The Gymnast. One incident in his short but splendid climbing career is rather bizarre: To treat himself for a case of frostbite, he plunged his hand into a vat of boiling glue. The result was a hand deformed into a kind of permanent claw, which he cheerfully rationalized as being of benefit for climbing! Owen Glynne Jones died on Dent Blanche in an accident in which he and a fellow climber were holding steady an ice-axethat was jammed horizontally in a crack and being used as a boost for a guide to reach a hand hold. The guide couldn't retain his purchase and fell on Jones and his friend, and all three plummeted down the mountainside, pulling with them a fourth member of the party who had been stationed about 30 feet away. All, including a fifth climber, were roped together, and the last man desperately hugged the rock, waiting for the inevitable jerk - it never came, as the rope between him and the others had apparently been secured and snapped cleanly in two. This fifth climber, a gentleman named Hill, could not descend the route by himself, so managed to go a slightly different way and reached the summit, then down, collapsing in exhaustion and delirium from time to time. The day before he was killed, as he and W. M. Crook walked down the Arolla Valley, he told his companion, who had expressed surprise at the vast amount of climbing Jones was doing each week, "You see, there are only a few years in which I can do this sort of thing, and I want to get as much into them as possible." |

| The

First Bouldering Guide . . . It is possible that the first dedicated bouldering guide was published in 1916 in the journal of Fell & Rock Climbing Club of the English Lake District. Written by J. P. Rogers and entitled "Boulder Valley", it describes a number of problems in the Low Water area of Coniston. And, yes, the word problem appears in the text, as it does in previous literature about the area describing the efforts of the small group of climbers who founded rock climbing as a distinct sport in the period 1880-1900. "Problem", originally, was as likely to refer to a 100 foot pitch as a 15 foot boulder. As an example demonstrating the flavor of the BV article, here's a quote concerning a boulder called the Pyramid: "The northeast corner requires good balance and some care when making the foot change at the commencement, while the south end bears a somewhat evil reputation for difficulty. C. Grayson is reputed to have made it 'go', but the writer has not seen anyone do it, although the route is scratched in places." And, here, the author describes the Overhang on the Puddingstone: "The Overhang is a pure gymnastic stunt and consists in jumping for a projecting rock 8'6" from the ground and swinging up until it is under one's left armpit. Then with a sloping right foothold to assist, it is possible to draw one's-self up by means of a right handhold until a knee can be placed on the tongue. From here the rest is easy." The author concludes with the following admonition: ". . . in spite of their comparative proximity to the ground, on the majority of the courses described, a rope is essential." [ Note: The problem of discerning the origins of bouldering is complicated by the difficulty of separating what we now think of as bouldering (that is, if you agree there is such a common definition!) from the tradition of practice climbing , particularly toprope work. As a matter of fact, when I first formulated my ideas about bouldering, in the mid 1950s, I didn't exclude toproping, instead interpreted "bouldering problems" as moves or short sequences, usually of greater difficulty than that found on existing traditional roped climbs, done close to the ground frequently without a rope, generally having a dynamic component, and requiring some special strength or technique normally not seen on longer climbs. Sport climbing, of course, didn't exist then in America, and wouldn't for another twenty years.] |

|

Getting

Started Young . .

. Here's a young boulderer, with her shiny new boots. From the Journal of The Fell & Rock Climbing Club (1913). One can only speculate about her destiny - now in the distant past. Photo by Arthur Wells (1913) |