|

Origins of Bouldering |

|

Origins of Bouldering |

More

Early British Bouldering . . .

|

|

Geoffrey Winthrop Young (Mountain Craft, 1949) has this to say, reflecting on bouldering in Victorian and Edwardian times: "Bouldering is the pleasantest of off-day distractions; but too many men allow themselves to spend the time on the merely difficult. Its use should be for safe exercises on rules of style. When you can climb an easy block with your hands, or balance up a wall with such light finger-hold that a friend can pass his hand under yours, or have discovered how to solve a shelf-climb by a push hold and a twisting arm lever, you have made a fair test that will be of future use. To wrestle up pure difficulty, such as you would not attempt in exposed higher climbing, by dint of muscle and strenuosity, proves nothing and does no good; it only reduces the restful value of the off-day." Mantlepiece at Low Man - Climbers Club Journal No. VIII, 1905 |

|

|

|

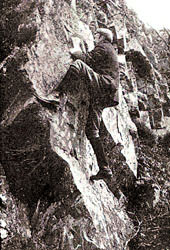

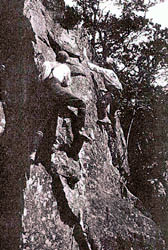

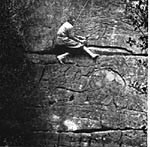

| Photo R. Adam ca. 1918 Photo C.E.Benson ca.1900 Photo C.E.Benson ca.1900 |

On the left, is Harold Raeburn, about 1918, striking what he calls a "Vertical Pose". To his right, are climbers at Castle Head, ca.1900. The center photo is entitled "Turning neither to the right hand nor to the left" and the description accompanying the photo on the right is "Dislodging the dangerous handhold. The nearer climber had designs of his own for reaching the stone, and nearly gratified the man with the camera, who kept protesting his anxiety to snapshot a slip. A fall here would be serious." - Crags & Hounds in Lakeland by C. E. Benson, 1902. In the center photo one can see how light, supple and well-made nailed climbing boots could be. They were made to fit, and not purchased off the shelf. It's a mistake to assume they were similar to the mass-produced, box-toed monstrous mountaineering boots with iron-hard rubber lugs used by the military in WWII, and adopted by climbers afterwards.( I should know - shortly after starting to climb I bought a pair of these.) |

|

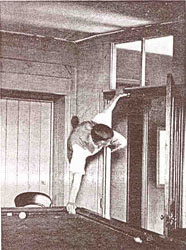

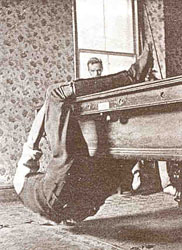

Meanwhile,

back at Wastwater

Lodge at Wasdale Head, rainy days and after-dinner time

saw lots of physical activity in the Billiards Room,

when climbers weren't traversing the famous barn door. Photos taken in the early 1930s by H. W. Lambert "Dinner over, the company is scattered about the hotel, yet every room seems crowded . . . Meanwhile the more energetic may be found in the Billiard Room . . . 'let's have the passage of the billiard table leg'. . . Only the gymnast succeeds; he begins by sitting on the table . . . he lets himself down gently, and, suddenly, twisting around, he braces his legs firmly against the cross-bars underneath . . . after a struggle his other hand and his leg appear on the opposite side of the table leg, and a moment afterwards he is sitting breathless on the table once more, amidst loud cheers." - L. J. Oppenheimer in The Heart of Lakeland, 1908. The gymnast was Owen Glynne Jones. The photos here of unknown climbers were taken 30 years later. |

Bouldering for the

Ladies . . .

Ruth Raeburn

(sister of Harold) designed the fetching women's climbing/bouldering

clothing you see on

the left, prior to 1920. Lest you think I'm stretching the point a bit

to include 'bouldering' here, listen to what she has to say: Ruth Raeburn

(sister of Harold) designed the fetching women's climbing/bouldering

clothing you see on

the left, prior to 1920. Lest you think I'm stretching the point a bit

to include 'bouldering' here, listen to what she has to say: "It is greatly to be recommended to the girl novice, and to all novices, to practise 'bouldering' as much as possible, and for the girl, to select those boulder climbs where activity and balance are of greater value than muscular strength and arm-pulls. She will there, often be able to show a more experienced and much more powerful man, how a short piece of difficult rock can be climbed with ease and grace. Unless the climb is under ten feet in height, with a good turf landing, the rope should always be put on. Below that height no injury should occur to any young person who takes care to alight a la chat, on feet and hands at the same time. Bouldering is reputed to be bad for the skin. Gloves should always be worn. These ought to be thin and easy, without being loose. The shins may be protected by puttees. Unless the knickers have double knees, it is well to tie on protectors, both for the sake of the knees and of the knickers. These can be made of a couple of large handkerchiefs or old scarves. With gloves, puttees and knee guards on, an hour's hard boulder practice should not result in the smallest damage to the tenderest skin. Bouldering is of great use in teaching what small holds can be employed with safety - at a pinch - on great climbs. It has also a wonderful effect on improving the balance, and in teaching the correct attitude to assume, and efforts to make, on various kinds of holds. On a single fifteen foot boulder one may find a series of climbs containing all the characteristic difficulties one will encounter in a whole day's climb on a great rock - peak." - Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920 |

G. W. Young

(1876-1958) was not particularly enamored with bouldering, although on

occasion he succumbed to its seductions. In fact, he 'bouldered'

on the Eckenstein Boulder with Oscar Eckenstein at the turn of the

century. Here are his thoughts on the subject from Mountain

Craft (1949) and Snowden

Biography (1957): G. W. Young

(1876-1958) was not particularly enamored with bouldering, although on

occasion he succumbed to its seductions. In fact, he 'bouldered'

on the Eckenstein Boulder with Oscar Eckenstein at the turn of the

century. Here are his thoughts on the subject from Mountain

Craft (1949) and Snowden

Biography (1957): "The introduction to climbing customarily inflicted on novices is practice on single rocks, low cliffs, and erratic boulders, with or without the aid of a rope held from above. This 'bouldering' or problem climbing, may serve to discover a talent or encourage an inclination, but it is of little use as commencing practice. The scrambles are short. They give no opportunity for a ground-work in rhythm or for balance in motion. If they are easy, they are done at once on the head or the heels, and no one the better. If they are more difficult, muscle can either manage them - a bad error to commence with - or, if muscle fails the ground close below or the rope close above deprives failure and success alike of any training for the nerve or moral for the memory. Their real value is only for the expert, who has learned to treat every rock with the same respect, be it of five feet or of five hundred feet. They make fine riders upon special propositions, of toe or finger joint, once we have mastered the general principles; but beginners get more benefit from easy, continuous exercises on the simple rules - and ridges." (MC) .

. .

"Crags on lower slopes and foot-hills did not come into question as a true day's climbing. The boulder practice, such as we obtained on rocks near our base, on off or wet days, was a limited exercise which could do little to improve the technique of the time. It was not until the climbing infection spread over areas without hills, where the solitary outcrop of gritstone or sandstone played the part of the local mountain, as it did in the Peak District, that bouldering, as we called it, could come into its own as practice on a large scale, and produce its experts. Herford and Laycock were original and conspicuous examples of a truth which only became recognized fifty years later, that practice and progressive training on relatively low and technically difficult rocks of this character are the essential preparation for attempting modern severe rock problems." (SB) |

Siegfried Wedgewood

Herford (1891-1916), the

great Edwardian rock climber, and his talented fellow climbers,

John Laycock

and Stanley Jeffcoat,

are credited with bringing

respectability to practice climbing on gritstone edges and boulders.

According

to Eric Byne in High

Peak (1966), "The

three of them together

made one of the great teams in British climbing history. The appearance

of

this team in 1910 brought gritstone climbing to maturity." Siegfried Wedgewood

Herford (1891-1916), the

great Edwardian rock climber, and his talented fellow climbers,

John Laycock

and Stanley Jeffcoat,

are credited with bringing

respectability to practice climbing on gritstone edges and boulders.

According

to Eric Byne in High

Peak (1966), "The

three of them together

made one of the great teams in British climbing history. The appearance

of

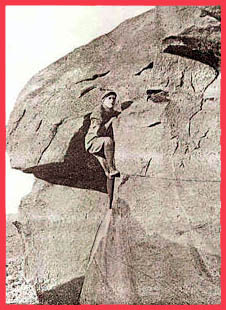

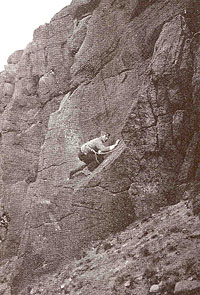

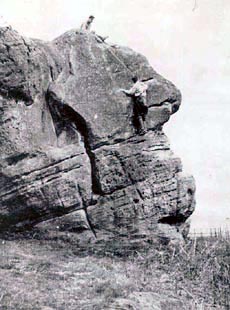

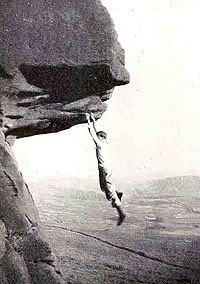

this team in 1910 brought gritstone climbing to maturity."Herford at Castle Naze ca. 1910 Blessed with a brilliant mind as well as the body of a natural athlete, Herford found a serendipitous outlet for his excessive energies in rock climbing. Gritstone climbing involved not only the boulders at the feet of many cliffs, but short, severe pitches on the cliffs themselves. Sometimes these were done on top-rope, sometimes they were led or soloed with little or no protection - climbing styles seen in America in the 1920s and 1930s and later at places like the quartzite bluffs of Devil's Lake, Wisconsin. Bouldering and top-roping were simply different aspects of crag climbing, the distinction having little merit at the time.  One

unusual practice

attributed to Herford was to down-climb a difficult pitch before making

its first ascent. He did this on the Great

Flake Pitchof

the Central

Buttress of Scafell in 1913.

He also practised jumping down to the ground from low pitches, as a

means of increasing his margins of safety. One

unusual practice

attributed to Herford was to down-climb a difficult pitch before making

its first ascent. He did this on the Great

Flake Pitchof

the Central

Buttress of Scafell in 1913.

He also practised jumping down to the ground from low pitches, as a

means of increasing his margins of safety.

Siegfried, an early aeronautical engineer with considerable mathematical talent, volunteered for service in the Great War. He applied for a commission, but was essentially ignored because of his German ancestry. He died of a grenade blast. Jeffcoat perished in the war, also. (Read Keith Treacher's Siegfried Herford: an Edwardian Rock Climber , 2000) Herford

on the Scoop,

Castle Naze ca. 1910 - photo by R. Hartley

|

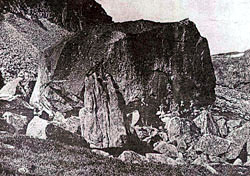

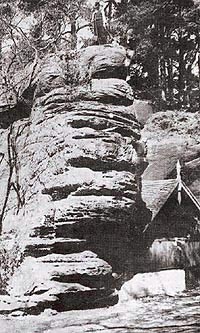

The Shelter Stone, about 1920, with a group of climbers |

Climber at Helsby - 1930s, by C.F. Kirkus  Colin Kirkus |

Colin Kirkus,

one of the best known British rock climbers between the two world wars

'bouldered' at Helsby

in

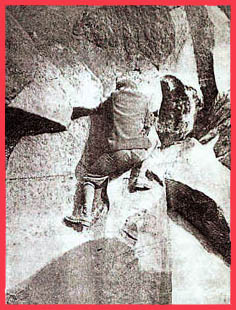

the 1930s. The red sandstone bluff above the village of Helsby offers climbs of from 20 to 50 feet, requiring gymnastic ability and strong fingers. Its friable nature prompted the use of a top rope by climbers in Kirkus's generation - at least on first tries. The standards at Helsby were exceptionally high, compared to other climbing areas in the British Isles. You can read about Kirkus in Hands of a Climber: A Life of Colin Kirkus by Steve Dean (1993). Kirkus was lost in a bombing raid over Germany during the Second World War. A. W. Bridge - one

of Kirkus' climbing partners - believed one should practice

falling, like his

predecessor, Siegfried Herford.

|

A. W. Bridge "bouldering" on the Curving Crack, Clogwyn Du'r-arddu Photo by C. F. Kirkus, ca. 1930 |

From Perrin's

description, there follows a list of 19 possible routes [or problems],

facilitated by a careful numbering of all handholds and lettering of

all footholds. An example: "Route B,

Hands 5 to 5 =

11 to 9, Feet G&H to F&E." Among

the problems thus described

for the 12 foot wall of rock, however, and according to Perrin, one or

two

of the moves are of technical grade 6a (roughly, harder

5.11). This

gives some indication of where theoretical limits of difficulty lay in

those

times. (Also, It brought a smile, for it so resembles a similar 'guide'

that

Yvon Chouinard and I did for the Jenny Lake boulders in the

Tetons

in 1958.) From Perrin's

description, there follows a list of 19 possible routes [or problems],

facilitated by a careful numbering of all handholds and lettering of

all footholds. An example: "Route B,

Hands 5 to 5 =

11 to 9, Feet G&H to F&E." Among

the problems thus described

for the 12 foot wall of rock, however, and according to Perrin, one or

two

of the moves are of technical grade 6a (roughly, harder

5.11). This

gives some indication of where theoretical limits of difficulty lay in

those

times. (Also, It brought a smile, for it so resembles a similar 'guide'

that

Yvon Chouinard and I did for the Jenny Lake boulders in the

Tetons

in 1958.)Photo of Edwards from one by Geoffrey Bartrum |

The Scoop Stone Farm Rocks ca. 1941  Hut Boulder High Rocks ca. 1941  Hellwall, Harrison Rocks ca. 1941 |

Although

the 1930s brought forth a new generation

of climbers who spent considerable time on small rocks near the larger

cities, many would have agreed with H.

Courtney Bryson, who wrote in Rock

Climbs Around London, "Even the

enlarged boulder problems described . . . are pranks, practice pitches

. . .

and proceed from the light-hearted joy which exists in the hearts of

those who love mountains and think of them often." Nea Morin writes, in 1946, "As children, my brothers and I climbed regularly on the rock outcrops on the Turnbridge Wells and Rusthall Commons, and some of the climbs we did were quite difficult . . . But it was not until 1926, after a visit to one of the extensive groups of sandstone rock near Fontainebleau, on which the Paris members of the Group de Haute Montagne had for many years made a practice of climbing at weekends, that I thought of exploring seriously the possibilities of my home town. The result was the discovery . . of the Harrison Rocks and the High Rocks . . . Many mountaineers tend to regard 'boulder climbing' as rather childish, and if it were to develop into an entirely separate sport there might, perhaps, be some justification for this view. There is no doubt, however, that this type of climbing affords excellent training . . . however fascinating this type of climbing may be, it should not be regarded as an end in itself, but as a means to an end . . . " E. C. Pyatt, the author of the guidebook (in which the above is an excerpt from the Foreward), Sandstone Climbs in S. E. England (1947), writes in the preface, "This book places on record the very considerable developments which took place on the sandstone outcrops in Kent and Sussex during the War years." He speaks, in the introduction, of British rock climbing : "No longer mere practice, it became eventually an end in itself and developed its own methods and traditions. Outcrop climbing [bouldering] has not yet reached this stage and it is questionable whether it ever will; it would not appear to possess sufficient potential for independent development to become a sport of its own." Of Harrison Rocks, where climbing had begun in the early 1930s, he says "Little new development took place until 1941, when E. R. Zenthon created a new fashion for London climbing by making a girdle traverse of the outcrop - a 'route' over 1,000 feet long with more than 20 pitches . . . Finally, in 1945 began a new wave of exploration under the inspiration of C. A. Fenner . . . the whole standard of climbing was advanced considerably . . . " Continuing, the author says "Rubbers (or klettershue) are the only suitable footgear, and nailed boots should never be worn." He adds, after alluding to the frequent use of top ropes, "Almost all climbs have been led . . . pitons have never been used on these outcrops, and certainly never should be." He does admit that in rare cases chockstones have been inserted in cracks. |

During

the 1940s, even with the war in progress,

there was much climbing activity on local rocks. In Climbs

on

Gritstone:

West

Yorkshire Area (1957), A. R. Dolphin

speaks of the climbing history of Almscliff Crag,

alluding to his

own not-insignificant contributions:

not-insignificant contributions: ". . . in 1939 A. R. Dolphin, then a schoolboy, had started his regular visits, and by 1940 was ready to attempt climbs of the greatest severity. Dolphin soon found an outlet for his exceptional skill by pioneering several new V.S.s, including . . . 'Demon Wall'. . . Dolphin on Demon Wall, photo by G.H.Chapman

A. Allsopp had demonstrated the physical possibility of 'Great Western' by his ascent with the moral support of a top-rope, but it was not until September that Dolphin succeeded in leading this ferocious course. . . in August, 1946, Dolphin surpassed himself by making the first, and for a considerable time the only lead of Birdlime Traverse. . . . For ten years virtually nothing new of importance was worked out; certainly a tribute to Dolphin's skill and eye . . ." Dolphin died in the Alps at the age of 28 in 1953 while traversing an easy slope. |

Social hour on Jeffcoat's Pinnacle 1942 Photo by J. M. Restall |

|

P. Biven on the first ascent of Quietus, Stanage Edge, in 1953. He uses a top-rope. Later, Joe Brown led the climb. There was little distinction made between bouldering and top-roping. Photos by K. C. Stringer |

|

| From the

1930s on British

climbers continued to practice on boulders, as well as on top-ropes

along many of the "edges", though lead climbing held considerably

higher status. Owen Glynne Jones, one of the first boulderers, says (in the late 1890s), "Of a truth, many of our prized little climbs in Cumberland are but slightly better than boulder problems." (He speaks critically here of the notion that British rock climbing can adequately prepare one for the Alps.) Later, in the 1934 CUMC Journal in a note about climbing in chalk pits, E. J. C. Kendall states, "It is not mere freak climbing, bouldering on peculiar rock, . . ." And in the 1944 CUMC Journal, in an article about the Harrison Rocks, A. H. R. Worssam says, "Nearly all the better climbs are hard, certainly worthy of a better name than boulder problems . . ." It wasn't until the last quarter of the 20th century that talented British climbers began to perceive their invention, bouldering, as a legitimate activity, equal in status to serious lead climbing. |