|

Origins of Bouldering |

|

Origins of Bouldering |

Oscar Eckenstein . .

. The First Documented

Advocate of Bouldering |

The first real bouldering personality, in all likelihood, was Oscar Eckenstein (1859-1921). He was the mountaineering companion and mentor of the bizarre and fascinating Aleister Crowley, with whom he climbed in both the Himalayas and Mexico at the turn of the century. He met Crowley at the Wastdale Hotel in the Lake District during climbing holidays in the 1890s. Eckenstein regularly roped-up with the Abraham Brothers, Lehmann Oppenheimer, and a few other climbing devotees at Wastdale, but it appears he spent more of his climbing time in Wales, meeting his friends, including Geoffrey Winthrop Young and J. M. Archer-Thomson, at Pen-Y-Gwyrd. Contributions to Climbing: Eckenstein, when he is remembered, is normally praised as an innovator, a technical theoretician, and a teacher, rather than as a great leader who boldly took his parties up intimidating new projects. This will become apparent as you read on . . . Technical Contributions: Eckenstein redesigned the crampon in 1908, so that it resembled what we wear today. In doing so, he introduced a bold new style of ice climbing. In addition, he created a grading system for a competition involving guides and amateurs using this device to ascend a glacier in the Alps. This may have been the first such formal competition in the history of mountaineering. He designed, constructed, and promoted a short ice-axe that could be used with one hand (blade length 18cm, shaft length 84cm). In this, he was sixty years ahead of his time. Both his crampons and axe were initially poorly received in England, perhaps due to the strained relationship between Eckenstein and members of the Alpine Club. He also published journal articles regarding knot-tying and the efficacious use of nails on climbing boots. All of the technical articles he wrote were accompanied by meticulous scale drawings, demonstrating his considerable mechanical and drafting abilities |

Eckenstein, upper left, and Crowley, right, in 1902 on their K2 expedition  Eckenstein at Wastdale Head Hotel, 1890s Photo Abraham Bros.  Working on an ice axe |

Photos Abraham Bros. ca. 1905  Eckenstein & Archer Thomson in Wales ca. 1905 |

Leading

or Following? He climbed in the British Isles, the Alps, Mexico, and the Himalayas, and was frequently part of first-ascent efforts in Great Britain, but very rarely led a rock climb there. The few extant photographs of him actually climbing show him holding the rope for someone else. George Abraham recalls only one instance in all the years he climbed with Eckenstein, in which the latter lead a climb: Moss Ghyll on Scafell. Bouldering - an Experimental Laboratory : When in Wales, Eckenstein's climbing partner was usually J. M. Archer-Thomson, who shared his appreciation of bouldering, where he learned his canonical balance technique under Oscar's tutelage. Rock Climbing Skills : Not leading, by itself, is no indication of a climber's gymnastic rock skills and general fitness. Although, obviously, it does say something about the trait of boldness revered by so many generations of climbers. O. E. was, no doubt, an accomplished 'rock gymnast'. Here's what Crowley had to say : "He [Eckenstein] was a finished athlete; his right arm in particular was so strong that he had only to get a couple of fingers on to a sloping ledge of an overhanging rock above his head and he could draw himself slowly up by that alone . . .He was rather short and sturdily built." Crowley continues: "His climbing was invariably clean, orderly and intelligible; mine can hardly be described as human. His movements were a series, mine were continuous; he used definite muscles, I used my whole body".  As

for his bouldering, Crowley

comments: "There is a climb on

the east face of the Y-shaped

boulder . . . near Wastdale Head Hotel

which he was the only man to do, though many quite first-rate climbers

tried it." As

for his bouldering, Crowley

comments: "There is a climb on

the east face of the Y-shaped

boulder . . . near Wastdale Head Hotel

which he was the only man to do, though many quite first-rate climbers

tried it." One does have to take what Crowley says with a little skepticism, however. He is known, on occasion, to have perfidiously vilified his enemies, and correspondingly, perhaps, to have overly glorified his friends. Nevertheless, there are several instances when others have made somewhat similar flattering comments about Eckenstein's climbing skills. |

| The Man:

Oscar Johannes Ludwig Eckenstein was born in Canonbury on September 9th, 1859, to a German father and an English mother. The father, a socialist, had departed Bonn in 1848, immigrating to England, where his politics were more acceptable. Oscar, a socialist who frequently denigrated the policies of his country, became an active member of the National Liberal Club. He had two sisters, Amelia and Lina. Lina, like Oscar, was politically active, particularly in Women's Freedom movements during the first part of the twentieth century. A medievalist, she was also a prolific writer in a variety of other topics. Several observers have concurred that Oscar belonged to a family having considerable intellectual abilities. Eckenstein had athletic and musical talents and did very well at gymnastics as a boy, as well as playing the bagpipes. As a young man he showed unusual scientific and mathematical aptitude and was educated accordingly - first, at University College School, and later, in London and Bonn, where he studied chemistry. He was an amateur carpenter and mechanic, and impressed many with both the breadth and depth of his knowledge in a variety of other, more technical or academic subjects. Eckenstein lived, at first with his mother, and later alone in his family home in South Hampstead from 1893 until his marriage twenty-five years later. He enjoyed mathematical puzzles and on one occasion forced Sir Gerald Kelly (brother-in-law of Crowley) to wait nervously in his hall as he set up, throughout the rooms of his home, an elaborate lay-out in order to attempt to solve a challenging problem: Kirkman's Schoolgirl Problem - introduced by the Reverend Kirkman about 1850 - for which Eckenstein assembled a bibliography, later published in Messenger of Mathematics (1912). He also compiled a collection of books, manuscripts, and original papers by Sir Richard Burton, whom Eckenstein seems to have greatly admired, presenting them to the Royal Asiatic Society before his death. H. W. Millhouse of Boston mentions having heard Eckenstein speak often of Burton, and of his and Sir Richard's strong interest in Eastern philosophies, particularly those related to mental telepathy. The Society, in the early 1950s, finally got around to examining this collection and members were astounded by the quality and quantity of material included. Of course, O. E. was long gone, and unavailable for the questions so generated. Eckenstein dressed shabbily and sported a bushy beard. In New York on business, according to a friend, he wore straw sandals, in bad weather or good. He preferred an old Greek fisherman's cap - perhaps befitting the image of a socialist he had of himself - and smoked pipes (that might have been found in the parlor of Sherlock Holmes), being addicted to Rutter's Mitcham shag. He had, by most reports, an abrading personality, and was not slow to show his displeasure. Very didactic and frequently irritating, when he felt he was right, the "coefficient of his mental elasticity was zero" (Crowley). On one occasion he became furious and called a meeting of the Climbers' Club to rebut the assertion that his leg had been 'shaky' while on the exploration of a new route, as George Abraham had implied when writing about the attempt. Thereafter, in his absence, a leg tremor due to prolonged strain was called by some, including R. L. G. Irving, an "Eckenstein". There is evidence that he was as concerned with debunking the claims of other climbers as he was in recording his own ascents, which he did in terse notes in hotel books. He had no tolerance for the Alpine Club, with its aging Victorian mountaineers, and many of its members shunned him as well, put off by his demeanor, his socialist leanings and his Teutonic and Jewish ancestry. He was quick to take offense, and even quicker to give it. However, Crowley mentions the fact that Eckenstein tried to teach him the art of controlling the mind, while on a climbing trip to Mexico. This tutorial was a result of Eckenstein's desire to disengage Crowley from what he felt were Crowley's ridiculous forays into what he called magick. Oscar Eckenstein, shabbily dressed, presented anything but an appearance of affluence. He emphatically stated that a "mountaineer should be a vagabond". However, appearances can be misleading. According to a relative who knew him well for over 14 years, Eckenstein was employed and drew a regular salary from the International Railway Congress Association, and was able to travel abroad - first class - whenever he wanted to. His fellow travelers mistakenly thought him an eccentric English millionaire. [When I discovered this, I thought immediately of Yvon Chouinard - not only are the two climbers roughly the same height and build, with, I suspect similar gymnastic skills, but both are intelligent & inventive, skilled artisans, both independently developed short, maneuverable ice-axes, both contributed to the design and use of crampons, and both shun "formal" dress. Chouinard calls himself a "wealthy dirtbag". And both of these superb climbers are not by nature reticent about expressing their opinions! Chouinard, however - considerably wealthier than Eckenstein - led on most of his best climbs and was proud of his widely acknowledged, bold spirit. ] As for the quality of his work, H. W. Hillhouse, who knew Eckenstein when the latter represented Great Britain at a meeting of the Congress in New York, remarks, ". . . I found O. E. to be years ahead of the times in thought and scientific invention of devices for the betterment of railroading . . . " Although Eckenstein had many enemies, no one denied his intellectual abilities. .

. .

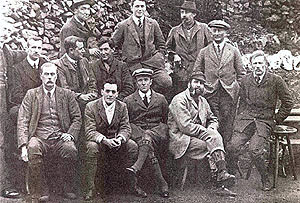

Photo of the Pen-Y-Pass Group: 3rd from left, middle row is George Mallory; top row, right is Geoffrey Young; far right is Archer Thomson; seated with pipe is O. Eckenstein - 1907, Photo A. W. Andrews |

Serious

Play: Crowley and Eckenstein made quite a pair. Here, Crowley gives us a glimpse (circa 1896) of a playful yet attentive attitude about trivial divertissements that most climbers demonstrate at one time or another: "On off days at Wastdale Head, it was one of our amusements to throw the boomerang. Eckenstein had long been interested in it and constructed numerous new patterns, each with its own peculiar flight. As luck would have it, Walker of Trinity came to the dale. He had earned a fellowship by an essay on the mathematics of the boomerang. The theoretical man and the practical put their heads together; and we constructed some extraordinary weapons. One of them could be thrown half a mile, even by me, who cannot throw a cricket ball fifty yards. Another, instead of returning to the thrower, went straight from the hand and undulated up and down like a switchback, seven or eight times, before coming to the ground. A third shot out straight, skimming the ground for a hundred yards or so, stopped as suddenly as if it had hit a wall, rose, spinning in the air to the height of some fifty feet, whence it settled down in a slowly widening spiral. Obviously, these researches bore on the problem of flying. Eckenstein and I, in fact, proposed to work at it. The idea was that we should cut an alley through the woods on that part of my property which bordered Loch Ness. We were to construct a chute and start down in on a bicycle fitted with movable wings. There was to be a steam launch on the loch to pick up us at the end of the flight. We were, in fact, proposing to do what has now, in 1922, proved so successful. But the scheme never went further than the construction of the boathouse for the launch. My wanderings are to blame." (Confessions of Aleister Crowley, 1922) Despite the considerable differences in personalities, Crowley and Eckenstein were very close friends. Shortly after Eckenstein's death, Crowley penned his recollections of the man in what would be the Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Here is a lengthy excerpt from that work which includes a putative mysterious, almost magical incident that befell Eckenstein, as well as humorous and/or revealing anecdotes, one of which involves Eckenstein's friend "Legros", the son of the famous painter, Alphonse Legros. : Crowley on Eckenstein . . . The Alps:  1890s A Strange Phobia . . . According to Crowley, Eckenstein feared only one thing: Kittens. He could deal with full grown cats, but had an intense aversion of their more youthful incarnations. Bouldering and the Creative Spirit : The appeal of mathematical and scientific work, his very precise nature, his love of climbing and his gymnastic talent may have influenced O. E. to focus what at that time would have seemed to be an unusual amount of his climbing energies on boulders, exploring and perfecting technique that would advance difficulty levels on longer routes. It seems clear, though, he was bitten by the bouldering bug and enjoyed the sort of strenuous play that became popular fifty or sixty years later. He may have been the first climber to appreciate bouldering for its own sake.  Victorian Pre-Balance Climbing Eckenstein was seriously opposed to publicizing climbing for a mass audience. Because of this, perhaps, and a quarrelsome, non-accomodating nature, one finds scant reference to him in mountaineering literature of that period. Alan Hankinson says "For him climbing was a personal, private, almost mystical experience, more a matter of communion than of community, something that might be damaged irreparably by vulgar publicity." This attitude put him opposite Owen Glynne Jones, who used every opportunity to publicize his adventures. By doing so, however, Jones initiated a change in paradigm and is now remembered as the first great gymnastic rock climber, whereas few know of Eckenstein's considerable contributions to bouldering, rock climbing, and ice climbing, although his trips to the Himalayas are fairly well documented. |

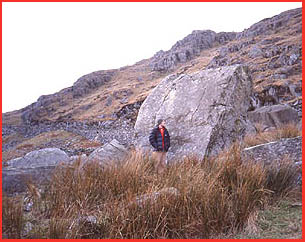

Geoffrey Winthrop Young, in Snowdon Biography (1957), comments: "In the same transitional period [circa 1900] , Oscar Eckenstein, an engineer, with a build and beard of our first ancestry, was, I believe, the first mountaineer in this or any other country to begin discussing holds, and the balance upon them, in a theory with illustrations. He had moved up with Frederick Gardner from Pen-Y-Gwyrd to a shack at Pen-Y-Pass, which he had fetched out of the Snowdon mines, and as I watched him hanging ape-like from the rock face of his eponymous boulder below the wall, and then passed my hand between his lightly-touching fingers and the rock, it was the first suggestion of the balance and foot climbing later analyzed in Mountain Craft." These observations are consistent with remarks made by Eric Newby in A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, as he relates his efforts to learn to climb in Wales in the 1950s: "After a large old-fashioned tea at the inn with crumpets and hard boiled eggs, we were taken off to climb the Eckenstein Boulder. Oscar Eckenstein was a renowned climber at the end of the nineteenth century, whose principal claim to fame was that he had been the first man in this or any other country to study the technique of holds and balance on rock. He had spent his formative years crawling over the boulder that now bore his name. Although it was quite small, about the size of a delivery van, his boulder was said to apparently embody all the fundamental problems that are such a joy to mountaineers and were proving such a nightmare to us. " [For a good look at modern bouldering in Wales, read Simon Panton's North Wales Bouldering/Bowldro Gogledd Cymru] |

Eckenstein Boulder Photos Simon Panton 2004  |

| Oscar

Eckenstein Speaks . . . In 1892 Eckenstein joined Sir W. M. Conway and several others on a scientific and climbing expedition to the Karakorum Mountains. He later compiled a diary of his time there, entitled Karakorams and Kashmir (1896). This is an entertaining little book that provides perceptive insights into a complex and often profane personality, jovial at times, and cruel, even violent, at other times. E.g., ". . . when my language ceased to be polite, though it retained its Anglo-Saxon character, they obviously understood - but they did not clear off. Ultimately I retreated on board our boat, and told the bearer to exterminate any natives who might turn up." And, later, "I calculated afterwards that it must have taken something like ten thousand curses to get them ['coolies'] over that pass, not to speak of a considerable amount of personal violence." He enjoys shooting and pops off quite a few birds with a fellow trekker's gun that fits him so well he refers to it as a "poem". From most sources one learns that he made his living as a railway engineer, though, in the text at one point he is asked by a native Colonel : "Did I work for a living?". His reply : "sometimes", leading one to suspect he thought of himself more of a vagabond than were his fellow climbers - mostly professional men - back at Pen -Y - Pass in Wales. He speaks of having been in South Africa, and at the end of this trip talks of an upcoming commitment in south India. Eckenstein loves to smoke his pipe : ". . . I smoked native tobacco with much enjoyment. It had a rather curious but not at all unpleasant flavour, due to the admixture of a little Indian hemp; but this I did not mind at all - in fact, I very soon began to consider it an improvement." As to his equipment : "The inside of my tent was rather amusing - the number of articles in it which have belonged at various times to various friends was large. I had an excellent cap, presented to me by T_ . . .I also had a second cap bestowed on me by La_ . . . I had an old Tartan comforter, contributed by friend Le_ . . . My coat was , strictly speaking, not my coat . . it belonged, or had belonged to O. W_ . . . As for my flannel shirt . . . I think it came to me through D_ . . . a thick-knitted jersey contributed by Bruce . . . a cushion . . . of which Conway used to consider himself the owner till I mildly but firmly appropriated it, much to his amusement . . . a red handkerchief, late the property of the aforementioned Le_ . . . a pocket knife which I confiscated from F. W_ . . . a tobacco pouch I once found on a train . . . the pencil I wrote with used to belong to J_ ." Very much the wandering scientist, he took an abundance of instruments on the trip with which to make geographical, atmospheric, and physiological observations. About half of these malfunctioned, and he became furious when another member of the expedition used these faulty devices to record measurements for the Royal Geographical Society. He exhibits knowledge of metallurgy, and is skillful at discerning imitations from precious stones. His mathematical background is apparent when he mentions a rope bridge, hanging in the form of a catenary curve, and, later, describes his pony as liking epicycloid curves, rapidly performed, and even chortoids. He is capable of consuming prodigious amounts of food. After a period of skimpy rations, he and a friend chow down with gusto in a native village : "Bruce and I had two chickens fried in butter, a dozen fried eggs, half a dozen large chaputties fried in butter, and half a gallon of milk. We were really too tired to eat what . . . would have been a square meal, and we slept like tops. . . We woke at 6 am . . had three quarts of milk, a dozen fried eggs, ten fried chops besides chaputties fried as usual. I had another quart of milk at am, and at 10 am we concluded the time for lunch had . . . come.. . .we had nineteen fried eggs and chaputties. . . I passed the time in writing having another quart of milk . . . dinner . . intended to be on a modest scale, consisting of a chicken and ten chops . . . ten eggs as well." On the 17th of July, 1892, Oscar left the expedition at Askole, having encountered (provoked?) friction among the ranks. Concluding he had little or no chance of doing a big alpine climb, without equipment and by himself, he turned to bouldering: "There are any number of exceedingly good boulders hereabouts, and I spent much time not only in climbing them myself, but also in setting natives to climb them. I arranged regular rock-climbing competitions among them, my object being to see how these natives compare with Swiss guides. I was more than surprised at the feats performed, and arrived at the following conclusions ( . . . considered from the boulder-climbing point of view). The best man I found would beat the best guide I have ever seen with the greatest ease over any kinds of rocks. For 'Platten' (smooth slabs) most natives would beat the Swiss. For climbing depending on small holds, the average native would be beaten by the average guide; but the difference is not great. As for 'friction-climbing' (rounded smooth rocks), there is not much to choose. The best native I found was not altogether an exceptional man here, as several ran him very close. I take rock-climbing here simply from the gymnastic standpoint. Their judgment of rocks was not good; in fact it was singularly bad, considering the quality of their performance. It is great fun starting the native at this sort of thing [bouldering] : the promise of the smallest copper coin of the country . . . as prize is enough to set the whole village off trying rocks. . . On thursday I stopped at Biano and held my great competitions. With regard to rock-climbing, my general conclusions at Askole . . . were confirmed. . . I tried to test their tree-climbing qualifications, but without success. The most difficult tree I could find was only twenty feet from the ground to where it branched off . . . the champion rock-climber was called Ghulam Ali, and he was presented with the large sum of one rupee." . . . . . |

A Magazine Article : In the May,1900, issue of Sandow's Magazine of Physical Culture there appeared an article written by Eckenstein entitled "Hints to Young Climbers". Eugen Sandow (1867-1925) was the first of the great modern bodybuilders, and a Google search yields considerable information about his life - which coincides, in period, with that of Eckenstein. Like O. E. he was of Teutonic ancestry, but spent most of his life in England. And, like Eckenstein, he possessed a considerable intellect. It seems highly probable that they knew each other, perhaps sharing information relating the two physical cultures they represented. Here are a few excerpts from that article, providing evidence of a unique mind; although some have criticized the overall effort as pedestrian and commonplace for that time. I've added emphasis on passages I think particularly interesting by using bold type. ". . . mental qualities, in the present state of Mountain Craft in England, most require to be developed. . . . the average man is certainly physically able to do pretty well all that is required; if he, however, wishes to climb very difficult rocks, he will find it useful to to develop certain individual muscles in his fingers . . . and a very few weeks of really hard rock climbing will develop these muscles to quite a considerable extent." "Climbing is, as far as I know, the only sport in which the absolute humbug can reign supreme without instant exposure. . . . believe nothing that is told you about mountain craft, unless you have absolute proof that a real expert is speaking." " . . . I am sure of being able to produce, in one season only, from any ordinary sound youth of fair strength and endurance, and with the necessary brains, a climber considerably in advance of all Englishmen today, except, perhaps, half a dozen. . . . the next question is 'How to begin?'. Unless you are acquainted with an expert, you will be best alone. . . . go to Wastdale Head . . . when there is no ice or snow . . . a pair of strong shooting boots, well nailed with wrought-iron nails, is quite sufficient . . . walk over the mountains, finding and doing some of the easier rock climbs . . . On your way you will occasionally come across boulders, which are so placed that it will not injure you if you slip off them when you try to climb them. Climb these boulders by as many ways as you can devise. Should any special way prove too hard for you, do not therefore abandon it, even after several failures. With any luck you will eventually succeed." "Gradually increase the rigor of your rock climbs; eventually you will try the really difficult ones, for you will have learnt not to slip, even on a place which is beyond your powers. The principal muscles to be developed are those which enable you to support your whole weight, or part of it, on a couple of fingers bent close to the palm, as the only holds which are not natural to the athlete are tiny cracks in the rock or little scooped-out ledges with a sharp vertical edge." "You are now fairly fit to tackle a big mountain . . . assume you decide to take [alpine] guides . . . you will be vastly superior, even on the road they know so well. And if bad weather comes on, as with luck it should, you may very possibly have the gratifying but wearisome experience of using your physical culture to persuade totally demoralized men that all is not lost, and that they had better walk home." "The great principles of rock climbing only apply to rocks of moderate difficulty. When a 'bit' of exceptional nastiness turns up one must e'en get up the best way one can. Many short pieces of rock exist where a special fingerhold, or a curious way of twisting the body, or a start face out, or even a jump, may be required. . . . There often are places on rock climbs of unusual severity, where the mouth, chin, elbow, knee, or any other part of the body may serve as an auxiliary hold . . . A boulder at Zermatt, now blasted away (the boulder, not the village!), was only climbed by holding on to a projection with the teeth." "The rope is merely a useless encumbrance on moderate and safe rocks . . . On really difficult rocks it saves time, as the second man can come up with freedom and speed. . . . Solitary climbing is very nearly as safe as any other; only sometimes one has to turn back. Also we do not recommend it for experts, but for beginners only . . . [Reader, I challenge you to provide rationale for this peculiar statement! I'll not reproduce here what Mr. Eckenstein has to say. If you are especially curious, send me an e-mail and I'll explain his reasoning . . . Remember, this was written about 1900.] "By the time you are yourself expert you will have acquired a large circle of devoted enemies. Every weapon that falsehood, scandal, and misrepresentation can forge will be raised against you. The 'Authorities' will refuse to recognize any new climbs you have made; and the Alpine Club will have none of you. All this will amuse you." [My thanks to the Alpine Club Library of London for their kind assistance] |

Eckenstein . . . the Wanderer In The Heart of Lakeland (1908) by Lehmann J. Oppenheimer (probably the Le_ mentioned by Eckenstein, above), the author, in Chapter XI, describes a long conversation among several climbers at the Wastdale Hotel smoke-room. It is difficult to ascertain whether Oppenheimer is reporting an actual discussion he participated in, or if he merely uses this as a vehicle to paraphrase several climbing friends in order to give the reader some understanding of how they think. Although names are avoided, one of these gentlemen is referred to as The Wanderer. There can be little doubt this is Oscar Eckenstein. The following are a series of quotations from this book that will give even more substance to the character of the fascinating, but perplexing, Eckenstein . . . "In the place of honour, by the fire, as of right, sits the Wanderer, listening for the most part, with an amused, tolerant expression playing round his grizzled mustache and beard, but breaking out at times into the most dogmatic and unaccomodating dicta . . . just now he is puffing quietly at his favourite down-curved pipe, waiting to be roused." : One of the gathering, looking at the hotel climbing book, where some youth has just entered a record of an exploit, says "Hm! - threading the rope - a shoulder up once more - are we to consider that conforming to the rules of the game, umpire?", addressing the Wanderer. Wanderer: "In my improved system of mountaineering, all aid, whether human or artificial, is absolutely forbidden in any circumstances whatever, and the offender is condemned to be hauled, between two guides, up Alps, provided with fixed ropes and spikes. The more the climber depends on his own brain and muscle the better, and the sooner you stop standing on each other's heads and shoulders, and using artificial aids on the rocks, the less chance there is that you will be made fools of by a few professional gymnasts and engineers. . . the essential element in mountaineering, as a sport, is the overcoming of difficulties; in proportion as they are evaded the sport diminishes, and the ideal mountaineer is the man who makes first ascents, alone and unaided." ". . . if you don't take proper precautions for your own sakes, I think you might for the sake of others. Don't all the leading authorities on climbing insist on the use of the rope?" Wanderer: " 'Sake of others!' Authorities!' what are authorities? Humbugs, sir; for the most part humbugs - the concentrated essence of ineptitude! Good of others, indeed! You are just as short-sighted in your altruism as the rest of the civilized world, that saves up all its weaklings in hospitals to propagate a debilitated race, and makes conventional hypocrites of its worthless members, instead of encouraging them to be themselves. If they only committed their crimes and were hanged, future generations might be saved from their leaven; and so with you and your rope. If you are anxious for the good of society, why, in the name of all reasonableness, don't you go unroped? If you're a duffer and fall and kill yourself, the world will be well rid of you, and you won't run the risk of dragging down a man the world's in need of." "But . . . why do you yourself always go roped if those are your opinions?" Wanderer: "Mine? Not in the least. I'm a hedonist. I've not been advocating altruism. They are yours, all of yours, taken to a logical conclusion." "If you want to make any improvements leave the sport and begin with the weather . . . " Wanderer: "I intend to make a fortune someday out of an aneroid for sale to hotels and boarding houses - warranted always to rise when tapped.; the subsequent fall to be managed stealthily when unobserved. A wetting never harms anyone, but worrying because one expects to get wet plays the very devil with enjoyment." "Now, a short line from Driggs is all that's wanted . . . and a tunnel through to Wastdale Head . . . Every peak and valley shall be accessible, but the access thereto shall be of no avail. . . " Wanderer: "Why not? Won't any places spring up for the greasy multitudes to get beer at? Besides, you don't consider that though there would be nothing for them to look at but scenery, they would have the satisfaction of annihilating the monopoly enjoyed by the few who come here at present. . . The obstacles in the way of reaching the best mountains at present weed out the unappreciative . . ." "And all the old shepherds shall be waiters and the farmer's wives and daughters rapacious land-ladies, eh? And the paths shall be made straight, and finger-posts plentifully supplied, that we may all walk therein . . ." Wanderer: ". . . I saw it happen so at Zermatt before some of you were born, and I foresee the fate of Wastdale Head. A road over the Sty will be the beginning . . . and several well-appointed hotels will naturally follow, with a guides' bureau beside the bandstand and telescopes in the parterres for watching the principal climbs. Next, a funicular railway up Gavel Neese . . . to a beer garden on the Gable top, with a station midway for visitors to the [Napes] Needle and Aretes. Performances on the Needle might take place at stated times in correspondence with the trains . . . cinematograph exhibitions of ascents would be given in the Wastdale Concert Hall at night. . . . the best view points on the mountain could be planted with seats . . . and the various routes on the crags could be indicated by splashes of paint, freshened up annually before the season. Danger-boards at the bottom of certain climbs have already been suggested . . . regulate the traffic by confining ascents to one route and descents to another . . . beggars might be licensed to yodel and make horn-echos in front of the precipices for the delectation of visitors." . . . . . . . . Eleanor Winthrop Young, the wife of Geoffrey, recalls: "I remember Eckenstein very well at a 1911 party, hammering things in the hall and smoking his awful pipe tobacco. He had a bushy beard at that time and was regarded as something of a prophet figure." . . . . . . |

An Aggressive Demeanor & Muscular Strength Belies a Constitutional Weakness : It may surprise the reader to learn that Eckenstein was asthmatic, as was his friend Crowley. In Karakorams and Kashmir, he makes virtually no reference to physical problems even remotely related to that condition, or of any other substantial internal difficulties. However, members of the 1892 expedition say otherwise: "[Eckenstein] had many of the qualifications of a mountain explorer highly developed, but his 'make-up' had one small weakness which is a terrible handicap in that part of the world, and that is a delicate interior." (General Bruce). O. E. had to leave the expedition owing to "ill-health and other causes" (A. D. McCormick). Sir W. M. Conway, leader of the expedition, describes Eckenstein as being so continuously unwell, that he was forced to send him back to London. [It should be mentioned that Conway, an Alpine Club favorite, and Eckenstein, did not get along]. And, in 1902, Eckenstein (assisted by Crowley) led an expedition to K2, which, although beset with a variety of problems, resulted in two members of the party reaching a height of 21,400 feet. Eckenstein not only endured an almost comical political ambush to keep him out of the region, but eventually came down with the flu. Heavy pipe smoking . . . ? The Aging Mountaineer: In his fifties, and apparently climbing very little, Eckenstein, nevertheless, was fascinated by the unsolved problem of ascending Mont Blanc by the Brouillard Ridge direct from the Col Emile Rey. He spent long hours examining this section through his telescope, feeling that it could be climbed via a flaw in the slabs of Pic Luigi Amedeo should the rocks be free of ice. This condition materialized in the summer of 1911, and Eckenstein notified a friend, Karl Blodig, who quickly journeyed to Courmayeur, and a few days later made the ascent with G. W. Young, H. O. Jones, and Josef Knubel, the famous guide. During the ensuing years of the Great War, Eckenstein volunteered and served as a special constable in London.

In February of 1918, at

the age of 58, he married Margery Edwards

and settled in

a village in the rolling hills near Aylesbury. Soon

afterwards,

he fell ill with consumption, and died in 1921. He left no children,

and his widow remarried.

A friend, J. P. Farrar, reports in the 1923 Alpine Journal, "I went to see (E) as he lay dying, one summer day two years ago, at the little hill town of Oving. His lungs had gone, he could only gasp; but his eye was as clear as ever, as dauntless as it had ever been in disadvantages of race, often of poverty, dying a brave man - wrapped up to the very end in his beloved mountains." Farrar's phrase "disadvantages of race", can be explained by another passage from Crowley's Confessions, concerning Eckenstein's deplorable castigation by some conservative British climbers : "My other climbing friends, with hardly an exception, came to me and warned me to 'have nothing to do with that scoundrel Eckenstein'. 'Who is he anyhow? A dirty East End Jew.' (I quote Mr Morley Roberts, the cobbler of trashy novelettes, who said this to me at Zermatt.)" The allusion to poverty is questionable, as is the reference to beloved mountains, should the expression be less than poetic : Oving lies at a height of 478 feet above sea level . . . |