|

www.johngill.net Origins of Bouldering |

|

www.johngill.net Origins of Bouldering |

Bouldering in America - Continued |

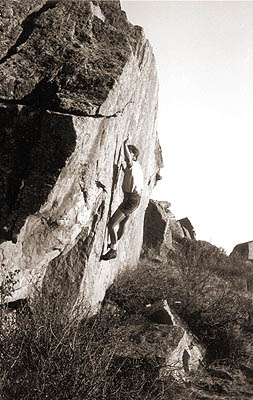

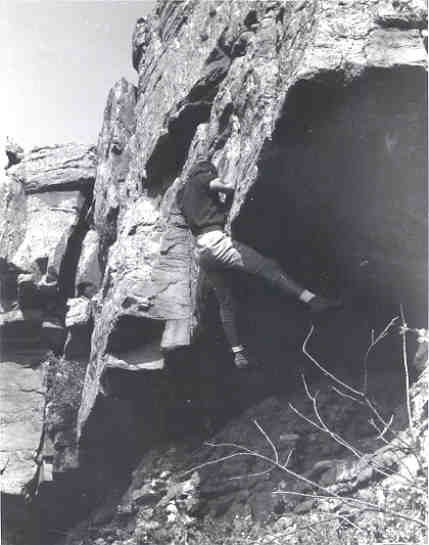

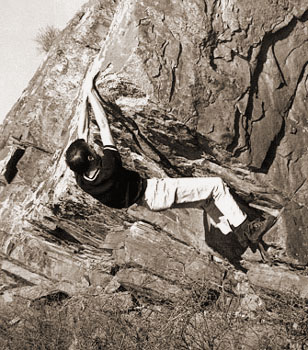

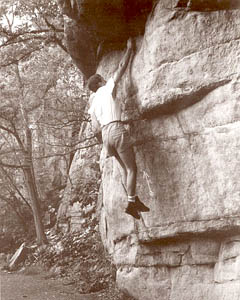

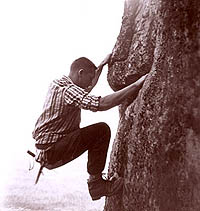

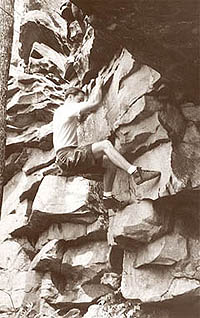

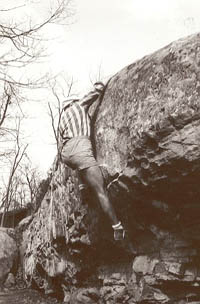

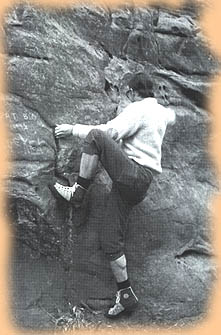

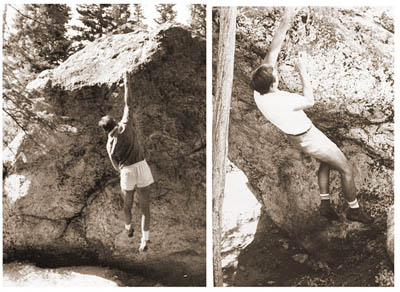

JG Left Eliminator ca. 1970  JG Soloing ca. 1968  Rich Borgman ca. 1968 |

Rich Borgman and I were the first to explore bouldering at Horsetooth Reservoir at Fort Collins, Colorado, starting in 1967. I was told by a local climber upon my arrival that Rotary Park had been a practice spot for a number of years. However, prior to 1967 no one had climbed on the boulders, although there had been top-roping on several longer pitches on the wall behind what would become known as the Eliminator Boulder. Upon arriving at CSU and finding that no one knew what bouldering was, I went to the school gym and asked the coach if he had any gymnasts who were climbers. He introduced me to Rich - a pommel horse performer - who had recently experienced a near-disastrous winter fall off the east face of Longs Peak, and was very receptive to my description of bouldering as a legitimate form of rock climbing. We became good friends and explored the boulders and ridges for the next three years. Rich finished an undergraduate degree in biology and started work on a masters in microbiology. He was married and had three small children. Having boundless energy, Rich worked part time in a biology lab and also cooked up breakfast pancakes at the local Village Inn. Somehow he managed to find the time to go bouldering three times a week. We climbed well together. I worked on an advanced degree in mathematics, was married and had one small child. I taught a couple of classes each semester to pay the bills, and generally had more time to spend bouldering and climbing. We both departed Fort Collins about 1971. On one memorable cold winter afternoon in 1967-68, I established the three basic problems on the rock I labelled the Mental Block. I did each of these the first try, but wore a top-rope because of bad landing spots. (There were no bouldering pads then.) On the boulder I called the Eliminator, I first did the right two routes, just to the left of the right edge, without a rope. In those days it was possible to do these climbs without actually using the right edge of the boulder. When I decided to try the problem on the left part of the broad face (the Left Eliminator), however, the bad landing spot convinced me to use a top-rope. I made it on the first try using a dynamic technique, but the swing I took on my left hand and arm made me particularly thankful I had roped-up! If I had come off the rock at the height of the swing without protection I shudder to think of the consequences. Later, I found a way to mitigate the swing and do the route fairly safely without a rope. The problems we did at Horsetooth were of modest difficult by current standards, and nowhere near as hard as many 21st century test pieces. Neither Rich nor I had the desire to work seriously on problems merely to establish levels of difficulty that would defeat others. Our time was spent exploring the area and climbing what seemed challenging and appealing and could be done in a few tries. We also repeated easy routes frequently. It took the arrival of Jim Holloway and others in the mid 1970s to set the competitive precedent of "seeing how hard a thing they could get up". After exploring new routes - I was never a 'counter', and I have no idea how many I did there - I would sometimes stop at the Roadcut and do my special contrivance: the gymnastic True Torture Chamber Traverse. This was not a simple but strenuous traverse of the overhanging face, as many believe, but a hand & foot hold-eliminate exercise that was fairly short but severe - it would probably be rated 5.13 these days. |

| The First Formal

Bouldering

Competition . . . ?

Ray Northcutt's frequent climbing partner, Harvey T. Carter,

was also a boulderer, living in Colorado Springs. Harvey was an

innovator. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he established the

American Mountaineering Association (AMA), devised

a complex

and poorly received rating system that he called the

Universal

Standard , and also organized the first invitational

bouldering

contest, the National

Championship Meet , held at the Garden of the

Gods. There were so few boulderers around, Harvey coordinated the event, set the course, acted as judge, and competed. I think he won. He invited me to participate, but I must have been involved in Air Force business at the time. This event was probably the very first "formal and open" bouldering competition in this country, and perhaps was the first ever (although the Bleausards or the British may possibly have done something like this before 1950 and Eckenstein conducted informal competitions in India in 1892). |

| The first recorded

bouldering at Vedauwoo,

a recreational area 16 miles to the east of Laramie, Wyoming, off I-80,

ocurred in the early 1960s. I may have stopped off in 1962, on my way

south from the Tetons, but I don't recall. What does seem fairly

certain is that a climber named K.

Hull climbed the corner route on his eponymous boulder

(now known as the Yosemite Slab) in 1963. According to Jim Halfpenny's

Guide Book of

1966, "A

twenty foot

tall boulder located just below the Friction Tower, provides climbers

with a fantastic assortment of routes. All routes on the boulder are

5.8 to 5.10 and require no protection. The rock was named for K. Hull.

The corner route is 5.8 and J. Horn's direct route is 5.9. P. Koedt has

done the standard corner route, no hands. Time required . . . forever,

route . . . limitless." Halfpenny continues, writing of the Mydlands Solo Tension Boulder (later, when freed, the Gill Seam), "Found by M. Mydland . . . A2 . . . only route on boulder. Usually requires about 30 minutes, 4 pitons and a free exit move." My thanks to Davin Bagdonas for supplying this information. While living in Ft. Collins between 1967 and 1970, I drove up to Vedauwoo a number of times and sought out new boulders and problems. Photos can be found on the homepage of this site. Jim Holloway did some mysterious bouldering here, as well. Who knows what V12s went unrecorded? Finally, it is entirely possible that Pete Sinclair and others did some bouldering here in the late 1950s, but there's no record of it - yet. |

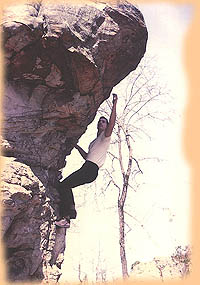

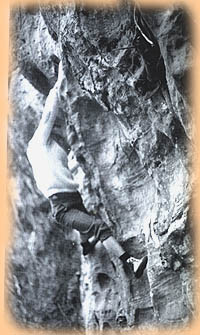

JG Vedauwoo ca. 1968 |

John Stannard ca. 1970  JG ca. 1964 |

Free climbing was introduced to the Shawangunks by Fritz Wiessner in 1935. He had begun climbing in the Dresden area of Germany, pioneering free climbs there in the 1920s. Although accepting the shoulder stand as a legitimate maneuver, he strongly opposed using pitons for artificial aid. It appears from some of the courageous leads he did in the 'Gunks, that he may not have countenanced top roping, but this author only speculates on the issue, never having met Wiessner. Hans Krause may actually have exerted a more profound influence on early 'Gunks climbing. But, whereas Wiessner viewed the short climbs there as perfectly legitimate climbing projects, Krause apparently thought of them primarily as practice for grander adventures. Neither Wiessner nor Krause bouldered in the area. Jim McCarthy and friends also started bouldering in Central Park about this time. When I made a couple of brief visits to the 'Gunks in the mid 1960s, I merely added a few additional problems to a number of existing ones. |

JG Georgia's Stone Mountain 1957 Photo G. Sutton |

JG Alabama's Desoto Canyon 1962 |

JG Alabama's Shades Mountain 1962 |

| I was probably

the first person to boulder

in the Southern United States,

starting about 1954 in Georgia on Stone

Mountain, a year or so after I began

climbing. In the early 1960s I bouldered in Alabama at Shades Mountain and DeSoto State Park, and in the mid 1960s I discovered bouldering areas in S. Illinois, Western Kentucky, Missouri, and elsewhere. |

| I

lived for three years in Murray, Kentucky (1964-1967), teaching

at Murray State. I bouldered in several areas in southern Illinois,

Kentucky,

and Missouri, never coming across evidence of previous bouldering,

although some areas I didn't explore apparently were visited by

climbers

for practice with ropes and pitons. Dixon Springs, Pennyrile Forest, and Cave-in-Rock were my normal destinations; I was usually accompanied by my wife and small child and sometimes a fellow faculty member or student interested in climbing. These were for the most part recreational outings, with very little competition - but they did serve the purpose of introducing bouldering into the heartland. |

JG Dixon Springs: Amphitheater 1964 |

JG Dixon Springs: Rebuttal 1964 |

JG Pennyrile Forest: Gill Bluff 1966 |

|

A

few years after

my departure some climbers in southern Illinois began to lay aside

their ropes and dabble in the sublime poetry of bouldering, although I

understand

that climbing and bouldering are now prohibited in the areas I enjoyed

. . . sad, but the world goes on. Royal Robbins bouldering at Makanda Bluff, 1973 Photos courtesy Gary Schaecher in Vertical Heartland (2005) |

|

JG Red Cross Rock Photos 1986 & 1963 Problems done 1959 & 1957 V9 & V8 |

Classic Cutfinger Crack in the 1960s - Don Storjohann starts the move |

|

Jenny

Lake Boulders

In Grand

Teton Park

in Wyoming, a few climbers had practiced on the three Jenny Lake Boulders

(Falling Ant Slab,

Cutfinger Rock(1987)

,

Red Cross Rock(1987) ) from the late 1940s through

the mid

1950s, when I got started there. About 1956 I recall watching

Dick Pownall,

a

Tenth Mountain Division veteran and mountain guide, along with Dick Emerson, a

naturalist ranger, pat the brown forest duff - drying their hands -

before trying Cutfinger Crack(5.9+),

As an example of the attitudes about bouldering held by older, traditional climbers in the early 1960s, the late Orrin Bonney, a well-to-do lawyer and a past president of the American Alpine Club, stated, in his 1963 Field Book:The Teton range : "The big boulders at the north end of Jenny Lake Campground provide a great deal of unconventional climbing, where the most expert tumble from holds no sane man would ever use on a mountain" . Orrin was reluctant to accept my prediction that within twenty years or so climbers would be doing such moves higher up, and would be trying dynamics far above the ground. These

are actually rather small boulders, and when I started climbing them it

took some ingenuity and a bit of contrivance to design a number of new

problems on the smooth pegmatite. But I was able to experiment with

both dynamics

and the use of chalk,

treating the three boulders as apparatus

for "gymnastic" exercises. This was an unusual approach to rock

climbing that reflected the perception of climbing as an extension of

gymnastics, rather than an extension of hiking.

Some of my problems were essentially ungradable, even using the B-system I devised: e.g., the one-arm (OA) problems and no-hands (NH) problems I did. For instance, center of Cutfinger(OA), classic cutfinger(OA), classic OH on Red Cross(OA), tiptoe-only routes on Falling Ant(NH)). I also practised harder individual moves like a gymnast would practice a specific stunt, probably just reaching what now are called double-digit V-levels. It was a time of experimentation. I was joined occasionally by Dave Rearick - an amateur gymnast like myself, who appreciated the interplay between the two athletic activities - as well as by Yvon Chouinard and Bob Kamps. |

| Boulder City,

near String Lake, is a more diverse

and much more recent development - perhaps first explored in the 1980s.

Most current Teton climbers who boulder go here. |

| I've recently been informed that bouldering was underway in the 1950s at Pete's Rock and Little Cottonwood Canyon by members of the Wasatch Mountain Club. Ron Perla tells me that in the Phoenix area Dave Ganci and others may have been doing some serious bouldering in the late 1950s. |