Bouldering at Flagstaff Mountain - The Early Years

by Pat Ament

Boulder's climbing history could be an encyclopedia, if a writer were to

delve more extensively into its possibilities. Of interest, but with no

likelihood of knowing their full stories, are early boulderers, such as

Corwin Simmons. I knew a fellow by the name of Dave Husbands who had climbed

with Corwin and attested to his remarkable ability. I knew Dave from Junior

High School. He was the smallest person on the heavyweight football team,

and a feared competitor. He invited me to try to tackle him one day, and

as I jumped up onto his shoulders he elbowed me hard in the solar plexis.

I was prone on the grass for about 10 minutes, trying to get my air back.

Dave was quite a good climber himself although quickly went another path,

after his young involvement with it. Through him, though, I had the second-hand

impression of one Corwin Simmons who apparently was of relatively small physical

stature. In heavy mountain boots Corwin had ascended the north face of a

boulder on Flagstaff Mountain that later was named after him.

This north face is very close to vertical, smooth but for a few ripply

layers that tend to underhang. The face narrows upward, like a pyramid,

finishing at a sloping crest that continues to the top. In one of my first

climbing classes, with Baker Armstrong, in about 1960, we stopped at Corwin

Simmons rock to try a few of its classic and interesting routes. No one

of the routes was easy for this collection of enthusiastic beginners. My

partner and friend, Larry Dalke, was in the class, and at one point he and

I slipped away from Baker's discussion group and started to play on the

north face. I knew nothing then of the significance of this little climb,

but Larry had gone to school with Dave Husbands and knew there was a famous

route here. Larry was half way up the face, by some mysterious ability to

adhere to what looked to be a holdless wall, when Baker turned and called

us back. He didn't want us to be off climbing by ourselves, unsupervised.

If I recall, Baker then spoke of Corwin Simmons and informed us that the

route we were trying was the hardest one on the rock, done in the early

1950's. That stuck in my mind, a sense of the seriousness of the route,

and I later returned, within the next couple of years, after I had done

a lot of bouldering, and managed, in good kletterschuhe (Kronhoeffer's)

to do the route. Today it's still a slippery, very thin face with tiny finger-nail

nubbins you scratch for balance, as your feet smear on the down-sloping

ripples. You have to fight not to simply step right off of it and drop to

the sloping, grassy ground. I can't imagine how difficult that route was

in mountain boots.

Now a lot of bushes have grown up and somewhat obscure the north face,

a historical climb hidden for the most part, although one can climb it by

pushing a way through the bushes to start and then having the bushes there

against your body on the lower half. I doubt any of today's boulderers would

even know the route exists much less view it as something they would need

to do. I suspect, however, that many of today's gym-trained climbers, with

so much upper-body strength, would feel every bit as uneasy on this climb

as we did years and years ago, as they would not be able to simply power

a way up. It would require balance, footwork, delicate technique -- so delicate

at times, that one almost has to hold his/her breath to keep from sliding

off.

As many of the good climbers of the early years around Boulder, Corwin

Simmons disappeared into obscurity and was never seen on the rock or heard

from during the golden age of the 1960's. Yet his spirit was felt, at least

by me, and I know by a few others, such as Larry Dalke, Dave Husbands, and

Baker Armstrong.

There were other names that circulated, such as Bob Beatty, Prince Willmon,

Ray Northcutt, and Dallas Jackson. None of these climbers viewed bouldering

as more than a little side fun to climbing, although each had talent. Prince

Willmon, of course, died tragically in a storm on Longs Peak and did not

have a chance to realize his talents. Bob Beatty, from whom I took a climbing

class at a very young age, was already quite "up there" in age. Yet he was

skilled on rock, a very quiet, humble man who knew how to use the mountain

boots he climbed in. I didn't know about Dallas Jackson, other than that

he was with Dick Bird, Chuck Merley, Cary Huston, and Dale Johnson on their

1956 ascent of Redguard Route, in Eldorado. Dick Bird led the famous "Birdwalk,"

the initial pitch on that climb, still a real forearm pumper (stiff 5.8+).

These climbers, along with Al Riordan, were no push-overs on rock. In the

1950's Cary Huston led a 50-foot off-width in Boulder Canyon that is still

a tough challenge today, the "Huston Crack." There were no "Friends" or

wide pitons in those days, and he led that slippery crack unprotected, which

certainly would make it at least scary 5.9 for me! That was, in essence,

a display of bouldering!

Another name is Tom Hornbein, who as far back as the later 1940's, when

he was geology student at C.U., was doing some impressive rock climbs. He

and Huston climbed, for example, a difficult crack on Longs Peak that ends

at Chasm View, and quite a number of classic climbs around Boulder have Hornbein's

name on them, such as Friday's Folly, on the backside of the Third Flatiron.

The real star, however, of this talented group, was Ray Northcutt. Not only

a master of the thousand-foot Diagonal Wall of Longs Peak, which he pioneered

with Layton Kor, Ray was known for his Flagstaff Mountain boulder problems.

In particular, on Cookie Jar Crack, is an overhanging wall ending with a

rounded top that appears to be absolutely smooth. When Bob Culp showed me

this problem, I couldn't imagine how anyone could climb it even using a tight

top rope. Northcutt had done it solo and, in one attempt, fallen and rolled

all the way down into the road below the rock. Hence, the name "Northcutt's

Roll." Culp, the best boulderer of the early 1960's on Flagstaff, didn't

go near the problem, and I could hardly imagine it was more than a figment

of someone's imagination, until one day in about 1963 my friend Larry Dalke

climbed it right in front of me, in his Hushpuppies!

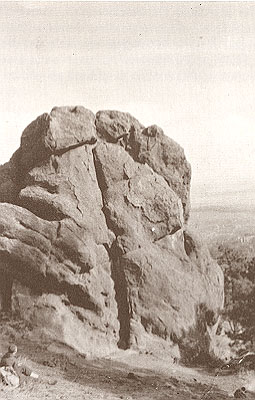

(Photo by Pat Ament - Larry Dalke looks at Cookie Jar in

1961)

The smooth, frictional Hushpuppies were Larry's private secret and foreshadowed

the better shoes we now have. He was able to lieback outward on tiny, brittle

flakes, as he smeared. He was a better boulderer than I was at that time,

although I later went more intensely into it than he. Larry's ascent proved

to me the wall could be climbed and that one could scratch a way up it and

over its rounded top. I later managed to climb the route, just once, and

never wanted to again. I can't imagine the shoes Northcutt wore, but I know

he had no chalk and certainly had worse shoes than I did when I made the

route.

Of course Northcutt became famous for his 1959 ascent in Eldorado of the

Northcutt Start, a 70-foot, extended boulder problem, in essence, now rated

5.11, and led by him when he was told by Ron Foreman that Kor had climbed

the route. Northcutt was competitive and believed he could do anything Kor

could. Instead of going on to be one of the country's greatest climbers,

as did Kor, Northcutt drifted away from climbing, as did many climbers of

his generation,

On the north side of Cookie Jar is a very strenuous bulge (in my best gymnastics

shape, I never found it easy), supposedly done by Dallas Jackson in the

late 1950's. I first saw the route climbed by Bob Culp in the early 1960's

when Bob took me bouldering on Flagstaff. He worked at Holubar Mountaineering,

and I met him there at the end of his work shift one afternoon. We went

straight to Flagstaff, and he was still in his suit. He put on his Kronhoeffers

and went smoothly up and over the big, rounded bulge, of Jackson Overhang

(or also called Jackson's Pitch), using little finger holds. I couldn't

even begin the climb. Had I been able to reach the holds, which stretched

Culp's six-foot tall, thin body, I doubt I could have done the route. I was

very humbled but also resolved to keep trying and to get better. When I finally

did the route, it was one of those big moments in my development, and I found

it every bit as hard as I had imagined. I never met Dallas Jackson, and I

have wondered if he indeed did do the first ascent of that route, or if Culp

made the first ascent and simply named it after Jackson. In any case, the

route shows how a single boulder problem can be the basis for respect, and

my respect remains for the mythical Jackson.

I also respected Bob Culp. He was the person who brought bouldering to my

attention, in the early 1960's, as something one could do independently

of longer rock climbs. I was immediately attracted to these short challenges,

especially to Pratt's Overhang -- a wall leaning steeply backward that Culp

waltzed over easily, at one point throwing his foot onto a horn about head

high and rocking up onto his foot and standing up. I was smaller than he

but had quite a time figuring out how to get my foot that high. I couldn't

imagine how, with his longer legs, he managed to do that move. It made me

feel very tangled up and awkward, and upsidedown. At last I learned how to

do the climb, and it felt like a real breakthrough for me.

One night, when Larry's parents and mine had a picnic together on Flagstaff,

Larry and I slipped away in the dark to find Pratt's Overhang. It was named,

incidentally, after an amazing Yosemite talent, Chuck Pratt, although Pratt

later told me he never had climbed it. So I always have presumed it was

another of those Culp routes for which he gave someone else credit. I don't

know if Jackson Overhang was first done by Culp, but I did in fact learn

Culp was the first to do Pratt's Overhang. Larry and I found the overhang,

and with him spotting I got up there, pulling on the strenuous holds to where

I had to throw my foot up nearly to my head and rock up onto it. I did it,

in the starlight, feeling quite happy, and stood there a second or two on

the knob, perhaps feeling quite cocky, with the difficulties over, and Larry

ambled away. He felt he no longer needed to spot me. To my surprise, I found

myself lying on my back in the dark, the wind knocked completely out of me,

and Larry pressing on my chest to try to get me to breathe. Somehow I had

managed to lose my balance in the dark, or my foot slipped off. I'll never

know. I landed flat on my back and very fortunately not on my head.

I recall standing up at one point, still no breath in me, and trying to

say, "Nice catch," but not being able to produce enough air to say a word.

I collapsed back down on the ground and let him press on me some more. When

I started to breathe again, we both began to giggle, and laugh, embarrassed

and feeling as though we had done something really stupid yet survived. My

wrist started to swell and hurt the next morning, and an X-ray revealed a

hairline crack. I was in a cast but continued to climb and boulder. The day

after the cast was put on, I did an aid climb in Eldorado, Mickey Mouse Nailup

(no easy climb), hammering in pitons with my left hand.

When I started to get better at bouldering, Culp brought me to an overhanging

crack on Flagstaff and said I might be able to make a first ascent. I was

excited and, my first try, went up the overhanging handjam of King Conquer

(a name other climbers gave the problem several years later). It was, perhaps,

the true beginning for me as a boulderer, to be followed by many years of

serious bouldering, and a wonderful preparation for finally meeting John

Gill, the Rembrandt of bouldering artists.