Recollections of an almost boulderer . . .

By Michael Fain

I got interested in climbing when I became a student at the University of

Chicago in 1952. Some friends had done a couple of guided climbs in

France the summer before starting college, and they hooked my interest with

their mountain climbing tales. So, we started a mountaineering club,

read everything that was available on climbing technique (not very much),

bought olive drab U.S. Army surplus nylon climbing rope and hiking boots with

Vibram lugged soles, and went on a climbing outing with the Chicago Mountaineering

Club to Devil's Lake, Wisconsin to learn the basics. Thus began countless

weekend trips through the 1950s to a premiere climbing area.

Climbing technique was rather rudimentary when I started. I

remember seeing hemp rope being used, and speaking to experienced climbers

who believed that if you needed protection, you shouldn't be there.

Hardware was scarce, and belay practices were often unsafe - the leader couldn't

fall. I remember that when I heard about a new concept called dynamic

belaying being used by the "new" California climbers, I excitedly did

the calculations of forces on rope (pre-woven) and climber, and our group

practiced safely arresting twenty foot free falls of a couple of railroad

ties under the football stands at the university. It was a basic tenet

of the time that climbing moves were supposed to be strictly static, and

three points of contact should be maintained on the rock at all times.

And, we diligently practiced that. Climbing was also not very

popular at that time, and most people thought we were crazy. When we'd

take our trips to Devil's Lake we would often find in the Spring and Fall

that we were the only campers in the campground, and in the Summer, when

there were a few more campers, the only climbers in the area for the weekend.

The bouldering concept was unknown to us at that time. Although

there were a few references to climbing on boulders in the literature of the

time, it never seemed like an end in itself. All our climbing at Devil's

Lake was done as practice and training for traditional climbing in the mountains.

( I remember scrambling up and down the talus field while roped to two others

because I had seen Joe Stettner leading climbers in the same practice).

There was no climbing guide to Devil's Lake at that time, but we knew about

a number of established routes (a majority by the Stettner brothers and the

Chicago Mountaineering Club) that would be considered 5.6 or 5.7, a very

difficult lead at that time, and more commonly done with a top rope.

So, we basically concentrated on practicing leading on countless easier 5th

class climbs wherever we found them on the cliffs, many of which I'm sure

were first ascents. We gave some of them names that are still used

today. Throughout the 1950s I put to use what I practiced by doing

traditional climbing in Colorado, the Tetons, and the Selkirks and Bugaboos

in British Columbia.

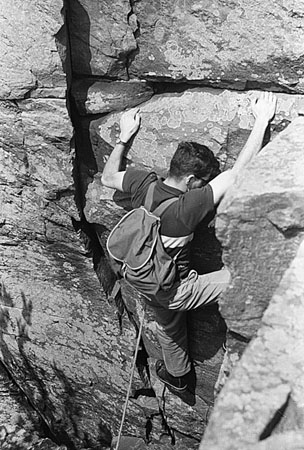

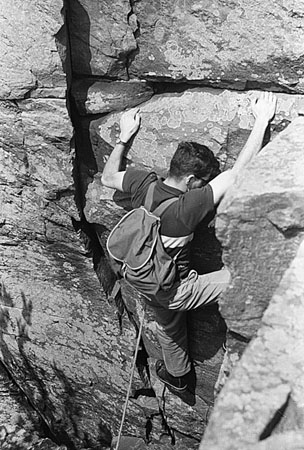

As our skills progressed, we did start doing more difficult pitches with

a top rope, but still as practice for improving our skills for the mountains.

But we avoided top rope routes which were difficult enough for us to fall

off several times because in those pre-harness days it was painful to fall

onto a rope around your waist. Eventually, we did start

to play around with what we considered very difficult moves that were only

a few feet off of the ground. And, when we could master the moves,

we started to eliminate the use of certain holds to keep increasing the level

of difficulty. While I wouldn't call it bouldering, because it

was still static and seen as practice for the mountains, it was a start in

that direction, although our standards were woefully low by contemporary standards.

The mid-1950s saw good climbers from Iowa, Wisconsin, and Chicago establish

a number of progressively harder routes. However, I was most significantly

impressed by the climbing of a mild mannered man, in his fifties, who

wore work boots (we were using lugged-soled Kletterschue by then).

Dave Slinger was an onion farmer who lived not far from Devil's Lake, and

he said he couldn't see what all the fuss was that the climbers, with their

ropes and equipment, made about climbing up rocks. He'd just free solo

up something that looked like fun to him, using a masterful, fast, free flowing,

non-static technique, that I'd never seen before. Dave would love to

wait near a difficult pitch close to the trail for climbers to come along;

then, he'd flow up the pitch and disappear, leaving the climbers with their

mouths open. That's how I first met him, and that was the first

time I'd seen a climber move dynamically, with fewer than three points of

contact on the rock for several moves in a row. Dave was probably

the first real boulderer at Devil's Lake: he believed hard pitches

were an end in themselves, and he used a self-developed dynamic technique.

Climbing for me really changed in 1958 when a stranger walked into the lab

where I was working at the University of Chicago, and said he was a new graduate

student and a climber, and he was looking for climbers to go to Devil's Lake

with him. He didn't, I recall, say much about his climbing experience,

other than he had some. It was an unforgettable experience watching

John Gill on his first climbing trip to Devil's Lake (I think he might have

been there several years before on a family outing). While walking along

the trail I innocently described Dave Slinger to John, and said he

used to regularly free solo an overhanging face of a twenty foot tower that

we were passing. So, John, without any preparation, started up the

overhang. Near the top he realized that he didn't have a good line for

the final move and calmly (at least it seemed to me) jumped off, twisting

in the air, to land safely on a sloping boulder as if he did that all the

time. Although I hadn't seen him do more than a couple of moves, I knew

that he was special, and that climbing wouldn't be the same. On a number

of trips to Devil's Lake with John, I had the good fortune to watch him establish

routes that were clearly the most difficult in their day. Through John,

bouldering became part of my vocabulary, and part of my climbing esthetic,

even though I wasn't very good at it. I remember complaining to John

that I couldn't get off the ground on his route on the Flatiron (V4) because

I couldn't reach the first hold that he used. To settle the question,

John brought over a rock, put it at the base of the climb, and suggested

that all was now equal. Equal, ha! I couldn't get off the rock.

Bouldering had arrived, and it was fun to watch.

Michael Fain, September, 2003