Historical Rock Climbing

Images

|

Page

8

More Early Images from the British Isles

|

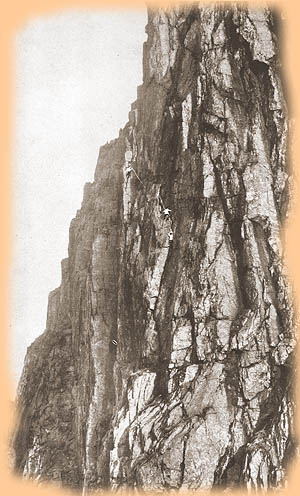

Bhasteir Tooth, Skye Three climbers - two to the left and below the obvious one. Photo Abraham Bros ca. 1910 |

When is a foothold a hand"hold"? Harold Raeburn on Salisbury Crags, Edinburgh, early 1900s |

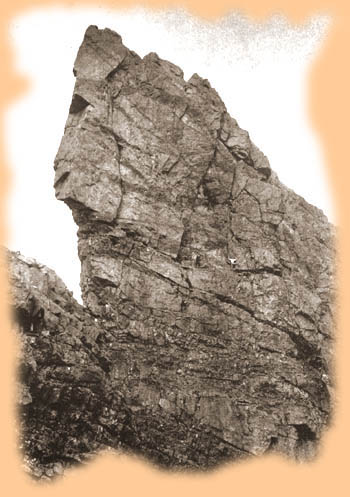

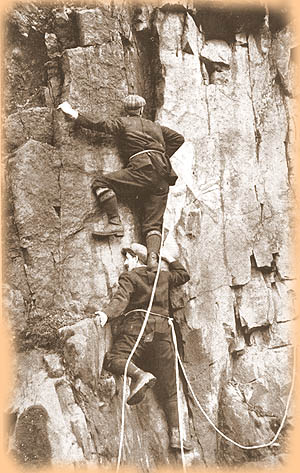

Central Buttress of Scafell

Lowest Climber is in the Flake CrackPhoto Abraham Bros. ca. 1920 |

|

|

|

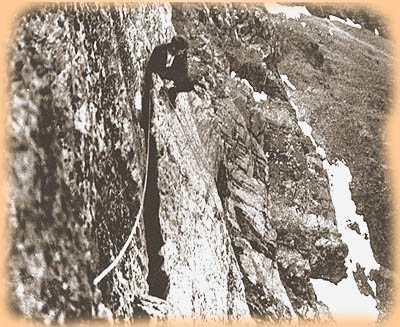

Siegfried Herford leading the famous Flake Crack on the Central Buttress, 1914. (E1 = 5.9) Photos G. S. Sansom |

Siegfried Herford entered climbing during H. M. Kelly's "4th Period", beginning 1903-1905, when British climbers moved away from ridges and gullies and onto slabs and walls. The ascent of Botterill's Slab [5.8] on Scafell in 1903 is the significant benchmark in this regard. (In Saxony, this period began approximately the same time - 1903 - with the ascent of Lokomotive Esse [5.6+] by Kunze and Perry-Smith). |

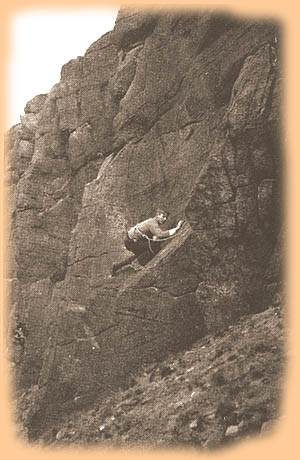

Fred Botterill on the first ascent of his slab route 1903 |

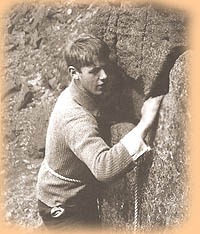

Siegfried Herford on the Scoop, Castle Naze ca. 1910 (5a = 5.9) |

A

hyperactive child with a brilliant mind, at the age of 18 Herford

entered Manchester University in 1909, excelling in mathematics and

technical studies, eventually becoming one of the world's first aeronautical engineers.

He also became Britain's most accomplished

climber, reaching 5.9 levels or above before meeting a tragic end in

1916 in the chaos of the Great War. Siegfried enjoyed soloing, and was

known to do risky

leads - e.g., he made the first ascent of Ilam Rock [5.7], a crumbling

limestone monstrosity hitherto "climbed" by throwing a rope over

the top and going up hand over hand. [Read Siegfried Herford: an Edwardian

Rock Climber (2000) by Keith Treacher]

Herford took down-climbing and falling safely very seriously, and - as mentioned - actually climbed down the Flake Pitch before making its first ascent. "There is a small school which believes that some practice in falls is well worth having! Herford belonged to it, who practised long jumps down into boulders . . ." - Dorothy Pilley in Climbing days (1935). |

| I

would guess there was little difference between Herford and

his close companions in Great Britain and Perry-Smith and Fehrmann and

associates in Saxony with regard to levels of pure climbing difficulty

during the period 1909 through 1916. Of course, the rock was quite

different in the two regions, making a more informed comparison

difficult. And the Germans were more accepting of artificial protection

than the British, putting the latter at a disadvantage on very steep

and exposed terrain. Geoffrey Winthrop Young speaks to this issue when describing an experience in the Alps ca. 1928 in Mountains With A Difference (1951)". . . . Of late years the corner is often climbed direct, but with the technical aids of pegs and snap-rings. I cannot regret that such safety-first methods did not enter into our mountaineering philosophy. It is a neat problem of technique, to learn how to attach oneself safely if artificially to rock at any moment of doubt, of excessive difficulty or of prolonged climbing strain. But it can never be as fine a trainer of skill, or set such a premium upon good nerve, climbing prevision and mountain knowledge, as the judgments which we had to learn to make before we launched - or refused to launch - our merely human power of attachment upon any long passage of difficulty, of danger, or of excessive nervous demand." |

Siegfried Herford & George Leigh Mallory Pen-Y-Pass 1912 Photo Geoffrey Winthrop Young |

A Typical Shoulder Stand ca. 1900 Photo

Abraham Bros

|

Dalton at age 33 Photo Mayson of Keswick |

The

Professor of Adventure

, Millican Dalton

(1867-1947), was an eccentric mountain guide who lived in caves in the

Lakes District. Here, Dalton and friends get a bit of exercise after

breakfast . . .

(Thanks to Mathew Entwistle for bringing Dalton to my attention.) |

Left to Right: Millican Dalton, Arnold Barker, Madge Barker, unknown. Quarries near Castle Crag 1919 Photo Mabel Barker |