|

Climbing and Gymnastics A Historical Association |

|

Climbing and Gymnastics A Historical Association |

The recorded use of ladders in gymnastics goes back at least to the late 1700s. It appears that sometime between 1778 and 1793, Johann Jakob Du Toit , while a teacher at the Philanthropinum in Dessau, Germany, introduced the oblique ladder as an apparatus to be used in physical education. He advocated walking up the rungs of the ladder without using the hands, and swinging from its underside and climbing hand-over-hand. GutsMuth, who taught at the Schnepfenthal Educational Institute from 1786 until the early 1830s, benefited from Du Toit's recommendations at the Philanthropinum, since the Schnepfenthal Institute was designed to imitate the Dessau facility. In the late 1700s, he used the ladder as Du Toit had recommended - standing against a wall - for student exercises. Here is the entire passage on ladders found in Gymnastik für die Jugend (1793), (my translation) : On Ladder climbing: "This practice in condusive to the maintenance of balance, to exercising caution in dubious situations, and to the strengthening of the hands and arms. We lean a wooden ladder against a wall; beginners learn without fear to go up and down. Then, as on a stairway, they go up without using their hands. They also practice on the rear or under side using the hands and feet. But as gymnasts, they also climb the rear side with hands alone, prohibiting the feet. In these situations the pupil is compelled to hang onto a rung, change hands on the rung, then reach for the next rung while his body hangs perpendicular. In addition, he might climb up the under side, squeeze through the rungs at the top, and descend on all fours, with the head down and feet above. Herewith he hangs carefully with a foot hooked over a rung, alternating hands moving down. Another, wanting to test his flexibility, winds like a snake through successive rungs, from top to bottom. A third climbs the ladder the usual way, but once up he circles to the underside and climbs down without using his feet. A fourth climbs to the middle of the ladder, clasps the ladder firmly, and turns it around so that its front becomes its back, against the wall. These little feats can be learned gradually. A ladder having eleven rungs is long enough. The gymnast must be ready to support and hold the beginner - only one can practice at a time."  The

small photo on the left is a scaled replica of Jahn's Der Zweibaum.

He had taken the climbing

frame, due (probably) to his predecessor J. Guts-Muth, and added braces

and inclined ladders. The

small photo on the left is a scaled replica of Jahn's Der Zweibaum.

He had taken the climbing

frame, due (probably) to his predecessor J. Guts-Muth, and added braces

and inclined ladders. |

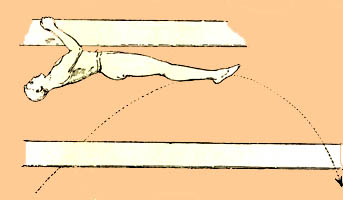

Wall ladders & stall bars in the Stockholm Central Inst., 1900 |

Finnish female gymnast on the horizontal ladders, 1912 |

Vertical ladder exercises were described by Ernst Eiselen (turntafeln) in 1837. Later, these took the form of Swedish Stall Bars & Swedish Wall Ladders . Eiselen first used the horizontal ladder, an exercise apparatus which still may be found in many gyms and physical training sites. Somewhat later, Adolf Spiess employed the horizontal ladder as the main apparatus for girls. Jahn constructed his first parallel bars by setting a ladder horizontally upon supports and removing the rungs. Its purpose was to develop strength for vaulting or side (pommel) horse exercises. |

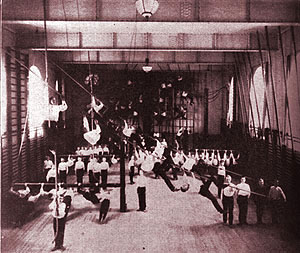

At

some point giant A-frame

ladders came into play for gymnasts.

Some of these were called Roman

Ladders, and were used in human

pyramid building. On the right is a drawing purportedly of

the gymnasium at the Round

Hill School in Boston in Northampton, Mass.,

circa 1826.

The experimental school opened in 1823, but closed nine years later. In

the background one sees gymnasts - not necessarily children - climbing

what seems to be

an asymmetrical A-frame

ladder.

At the Round Hill School the physical education curriculum consisted

of "running

(one mile in 6.5 minutes), jumping, leaping, climbing,

and Saturday afternoon hiking" It

would not surprise me to learn that some of the pupils climbed on local

rocks on these outings. At

some point giant A-frame

ladders came into play for gymnasts.

Some of these were called Roman

Ladders, and were used in human

pyramid building. On the right is a drawing purportedly of

the gymnasium at the Round

Hill School in Boston in Northampton, Mass.,

circa 1826.

The experimental school opened in 1823, but closed nine years later. In

the background one sees gymnasts - not necessarily children - climbing

what seems to be

an asymmetrical A-frame

ladder.

At the Round Hill School the physical education curriculum consisted

of "running

(one mile in 6.5 minutes), jumping, leaping, climbing,

and Saturday afternoon hiking" It

would not surprise me to learn that some of the pupils climbed on local

rocks on these outings. |

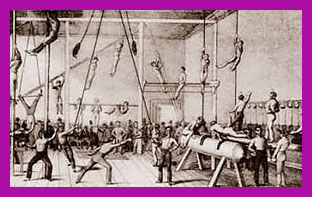

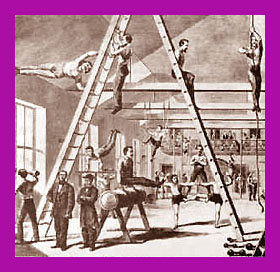

On the left is a drawing of an American Turner Gymnasium, circa 1860. Besides the state-of-the-art A-frame ladder, there is a side horse (now called the pommel horse), parallel bars, climbing ropes, dumbbells, pyramid formation, and possibly a set of rings. A climbing frame appears in the background. |

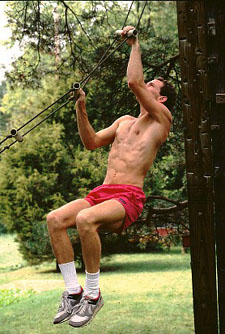

About

1980,

John Bachar- as a

training device for rock climbing - devised a rope & rung

variation on his oblique ladder that was portable, but introduced an

element of instability

into ladder-climbing. Climbers found that the Bachar Ladder

might cause elbow or shoulder injuries and had to be used with caution. About

1980,

John Bachar- as a

training device for rock climbing - devised a rope & rung

variation on his oblique ladder that was portable, but introduced an

element of instability

into ladder-climbing. Climbers found that the Bachar Ladder

might cause elbow or shoulder injuries and had to be used with caution. Eric Hörst,

from Training for Climbing

Eric

Hörst comments: "For

much

of the 1970s and 1980s, the Bachar Ladder was a

backbone exercise for high-end climbers. With the advent of the

fingerboard and indoor climbing gyms, however, the ladder has fallen

somewhat out of favor. Still, a well-conditioned climber can benefit

from an occasional session on a Bachar

Ladder . . . Only use Bachar Ladders constructed with static

line rope. The springy nature of a ladder made with dynamic rope may

lead to elbow tendonitis." He

warns of ". . . dangerous dynamic

drops during the down phase."

|

In the 1990s, campus boards - a kind of variant of a ladder created by Wolfgang Güllich in a university campus gym - replaced rungs with small ledges, producing a training device for arms and fingers very similar to natural rock surfaces. Campusing, from Training for Climbing |

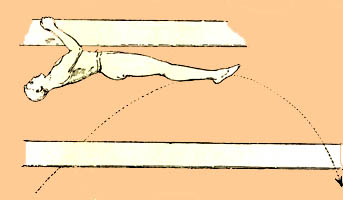

| Ladder

Climbing of the Future . . . Dyno Ladders would be great fun and would separate the men from the boys! Rules would include banning the use of the feet and legs on the ladder - only the hands could touch the apparatus. Adjustable rungs would encourage competition. Free aerials would be the order of the day! Muscular development would be a necessity - no more being punched out by skinny 14 year-old novice climbers and 80 pound female boulderers! No more contorted heel hooks or other athletic depravities - just pure macho flight! This is the future, men! Carpe Diem! |

(Thanks, Bruce McCall of The New Yorker, for inspiration!) |