Some

Recollections on the Origins of Bouldering in Australia

By Ted Cais

I was fortunate to have been a young protégé of Albert A.

Salmon, who pioneered the first golden age of Australian climbing

around Brisbane in the 1930's, and to have participated in the second

great era from 1960 to 1975, when technical difficulty approached world

standards, at least in the crack climbing developments led by Rick

White at Frog Buttress.

This background provides me with a unique insight into the origins of

bouldering there, even though it excludes similar interstate activity

in Sydney and Melbourne that evolved rather independently owing to

geographic isolation. These capital cities also had their local

climbing clubs and regional bouldering spots (Lindfield Rocks and

Hanging Rock, respectively) that were utilized from at least the

mid-1950's.

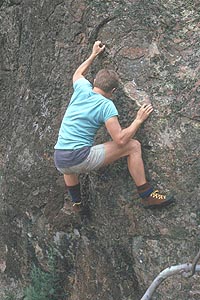

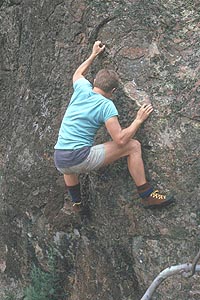

(Cais

on a John Moore boulder problem at Hanging

Rock, Victoria 1970 - Photo by K. Jensen)

Australia was first strongly influenced by Britain, being a far-flung

outpost of the Empire, but developed its own frontier spirit

appropriate to a new colony with vast spaces and a small population, in

contrast with England’s village culture. The area is blessed with good

weather and an abundance of crags close to urban centers. Early

climbing evolved as an extension of hiking (known as bush walking) and

focused on exploration and the capture of new summits by the line of

least resistance.

Salmon was a

tireless walker who achieved many first ascents of major

rock peaks in southeast Queensland. He was eccentric with

strong convictions and a personal ethic that excluded the use of rope

and other forms of protection as unsporting. For safety, he

relied on three points of contact with the rock and leg power, so

hiking long distances over rugged terrain was necessary and sufficient

training, although he did have natural gymnastic talent. His

favored climbing shoe was the plimsole or tennis sneaker (called

sandshoes in Australia) unlike the rigid nailed boot used

contemporaneously in England. He rarely sought out intrinsic

difficulty for its own sake because he had to be certain he could

safely stay attached if a hold broke and downclimb unaided.

Salmon was a

tireless walker who achieved many first ascents of major

rock peaks in southeast Queensland. He was eccentric with

strong convictions and a personal ethic that excluded the use of rope

and other forms of protection as unsporting. For safety, he

relied on three points of contact with the rock and leg power, so

hiking long distances over rugged terrain was necessary and sufficient

training, although he did have natural gymnastic talent. His

favored climbing shoe was the plimsole or tennis sneaker (called

sandshoes in Australia) unlike the rigid nailed boot used

contemporaneously in England. He rarely sought out intrinsic

difficulty for its own sake because he had to be certain he could

safely stay attached if a hold broke and downclimb unaided.

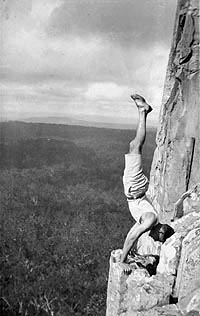

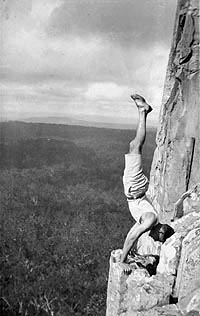

(Salmon

doing a head stand on the East face of

Crookneck in the Glasshouse Mountains, north of Brisbane circa 1929)

Perhaps his most visionary achievement was the first solo ascent of

“Fly Wall" at Katoomba, in the Blue Mountains just west of Sydney in

1934. This certainly can be regarded as a "highball" boulder

problem. Salmon’s usual limit (based on the three-point contact

rule) approached 5.6, but on that day he excelled himself under the

challenge issued by Dr. Eric Dark, another significant historical

figure in Australian rock climbing. The difficulty may well have

been 5.7, corresponding to the first “Very Severe” or VS on the English

scale.

Of course this difficulty pales in comparison to earlier European

achievements like those of Oliver Perry Smith (Elbsandstein) and Paul

Preuss (Dolomites) but Australia was so parochial at the time they had

to build local standards from scratch without the benefit of outside

knowledge. Salmon collected an extensive library of books, but

most were on Himalayan and Alpine adventures and hardly relevant to

technical rock climbing.

It took another 30 years for Australian standards to break the 5.10

barrier. The leading exponents in the 1960’s were Bryden Allen and John

Ewbank, both British expatriates living in Sydney. Their

firsthand experiences of overseas climbing and natural abilities

accelerated the pace of development to these levels in our neighboring

State of New South Wales. Allen brought the first PA climbing

shoes to Australia and invented the “carrot” bolt with removable

hanger.

I was still in high school in 1962 when Salmon introduced me to many of

his climbs, but his strict ropeless ethic inhibited my

development. I joined the school rowing team (crew) and started

weight training that soon conveyed benefits for climbing in a more

aggressive style utilizing upper body strength. Before then the

application of dynamic movement was regarded as inappropriate under the

old culture of "the leader never falls".

As far as I know I was the first Australian climber to systematically

train with weights and still believe the power clean with bodyweight is

one of the best overall exercises. Unfortunately the development

of climbing flexibility and finesse became neglected in this obsession

for raw power.

Up to this point bouldering never was taken seriously as a sport in its

own right. We had the conventional view it was a game or trifling

diversion from real climbing involving multi-pitch roped ascents of

large cliffs. Moreover there are few acual boulders in Brisbane

that, by virtue of limited height, would focus our efforts

suitably. The favorite training ground was Kangaroo Point, a 20-m

quarry face that encouraged toproping, although I added several hard

boulder problems on a smaller section of the cliff (W1).

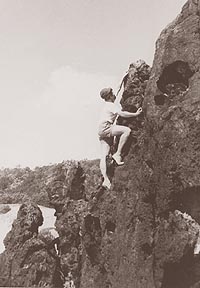

The sea cliffs at Noosa and Stradbroke Island were early popular

bouldering venues since the sandy beaches made for safe landings.

Salmon climbed

there extensively, even if this activity was

an adjunct to a social surfing party. Manmade structures like

buildings and bridges were popular too since they offered long

traverses at a comfortable height. Naturally these favored

endurance over absolute technical difficulty.

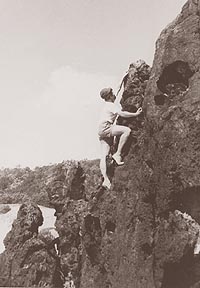

(Cais

bouldering at Point Lookout, Stradbroke Island,

1962 - photo by A.A.Salmon)

The closest classic boulders were in Stanthorpe, an outlying provincial

town where the surrounding fields are littered with coarse-grained

granite boulders. I first visited the area in 1962 with the

primary objective of scaling every boulder. Even the

simplest way up could be challenging thanks to the rounded and overhung

sides.

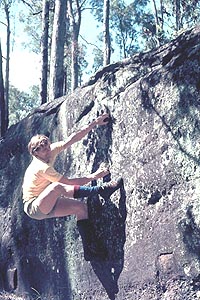

I would say bouldering for its own sake, that is the desire to execute

a specific sequence of intense movements, started in the early

1970's. This was enabled by our discovery in Toohey’s forest of a

small boulder field nestled in the trees of a local suburb that offered

a texture like gritstone with small nubbins to tweak on. For

the first time individual problems were marked, a circuit established

and difficulties attained V1.

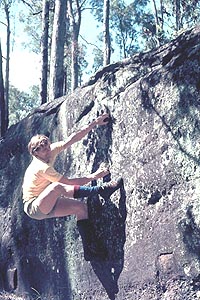

(Cais at

Toohey's forest in 1974 - Photo by K. Jensen)

(Cais at

Toohey's forest in 1974 - Photo by K. Jensen)

Around this time we outgrew our British heritage and learned of the

exciting developments in the USA that culminated in Rick White’s first

Australian ascent of The Nose and Salathe Wall in 1973. I was

inspired by an article on John Gill to try "chalk" in the same

year. Alas, I didn't realize it should have been magnesium

carbonate and used "rosin" instead. It was a short-lived

experiment that generated a sticky mess in the Australian heat!

Proper chalk was not adopted till after the visit of Henry Barber in

1975.

These early beginnings were replicated elsewhere in Australia at

similar times but none were significant breakthroughs in the wider

international context. These were left up to the Australian

tennis players, swimmers, distance runners and cricketers, to cite a

few sports. Still, these few pioneering climbers laid good

foundations for succeeding generations to participate with the best.

WEBSITE: W1 Kangaroo

Point 1968

http://members.tripod.com/tecais/

Salmon was a

tireless walker who achieved many first ascents of major

rock peaks in southeast Queensland. He was eccentric with

strong convictions and a personal ethic that excluded the use of rope

and other forms of protection as unsporting. For safety, he

relied on three points of contact with the rock and leg power, so

hiking long distances over rugged terrain was necessary and sufficient

training, although he did have natural gymnastic talent. His

favored climbing shoe was the plimsole or tennis sneaker (called

sandshoes in Australia) unlike the rigid nailed boot used

contemporaneously in England. He rarely sought out intrinsic

difficulty for its own sake because he had to be certain he could

safely stay attached if a hold broke and downclimb unaided.

Salmon was a

tireless walker who achieved many first ascents of major

rock peaks in southeast Queensland. He was eccentric with

strong convictions and a personal ethic that excluded the use of rope

and other forms of protection as unsporting. For safety, he

relied on three points of contact with the rock and leg power, so

hiking long distances over rugged terrain was necessary and sufficient

training, although he did have natural gymnastic talent. His

favored climbing shoe was the plimsole or tennis sneaker (called

sandshoes in Australia) unlike the rigid nailed boot used

contemporaneously in England. He rarely sought out intrinsic

difficulty for its own sake because he had to be certain he could

safely stay attached if a hold broke and downclimb unaided.

(Cais at

Toohey's forest in 1974 - Photo by K. Jensen)

(Cais at

Toohey's forest in 1974 - Photo by K. Jensen)